Consumer Risks and Rewards Amid Increased Competition in Kenya

by Annabel Schiff

Aug 17, 2015

5 min

Change is upon us. After eight years of market dominance Safaricom’s M-PESA seems to have finally met a potential contender, the banks. Data from The Helix Institute of Digital Finance shows that between 2013 and 2014 banks in Kenya (in particular Equity Bank) have aggressively grown their agent networks, and now account for 15% of the agent market share, up […]

Change is upon us. After eight years of market dominance Safaricom’s M-PESA seems to have finally met a potential contender, the banks. Data from The Helix Institute of Digital Finance shows that between 2013 and 2014 banks in Kenya (in particular Equity Bank) have aggressively grown their agent networks, and now account for 15% of the agent market share, up from 5% in 2013. In addition to increased touch points, banks have introduced a greater diversity of sophisticated offerings to the market, such as savings and credit. Both product development and the growth of the agent network are moving in the right direction to provide customers with more options, in a more competitive market.

Whilst celebrating this transmutation, we must also remain mindful of the risks these developments pose to customers, and how to mitigate them in order to drive trust and activity on the network. In CGAP’s recent publication ‘Doing Digital Finance Right: The Case for Stronger Mitigation of Consumer Risks’, seven key customer risk areas were identified. This blog will draw on three of these risks: (1) Inability to transact due to network and service downtime; (2) Insufficient agent liquidity or float impacting ability to transact; and (3) Poor customer recourse at the agent level. I also encourage you to read the three blogs preceding mine, which outline and delve deeper into the seven risks and potential solutions.

Inability to transact due to network/service downtime

Although service downtime has markedly improved in Kenya, with agents facing a median of two downtimes per month compared to nine in 2013, users still complain of system and network downtime preventing them from completing transactions, and posing significant risks as a result.

Over the years, platform migration has been a key area of investment for providers as they try to overcome restrictions on growth due to limited functionality and capacity. Following the trend, earlier in the year Safaricom upgraded to a second generation (‘G-2’) platform, now hosted and managed in Kenya and with the ability to handle up to 900 transactions per second.

For now, banks have a comparatively low number of transactions flowing through their systems. However, as activity increases they must remain cognizant of how much traffic their platforms can handle, how they communicate downtimes in advance to agents, and how they work with telcos to ensure advanced warning about mobile network downtimes. Our Kenya ANA data reported that only 17% of bank agents, compared to 85% of telco agents, receive prior warning of downtime.

Insufficient agent liquidity or float impacting ability to transact

In 2013 and 2014, Kenyan agents ranked ‘lack of resources to buy enough float’ as their second biggest barrier to increasing daily transactions. This is mirrored in Intermedia’s demand side data, in which 55% of Kenyan users interviewed said they ‘had problems with an agent lacking sufficient e-float and sufficient cash to complete transactions’.

Extending credit to agents is often cited as a quick win in terms of alleviating liquidity issues, but it may be more complex than we may think. During interviews carried out with 40 agents in Kenya, some interesting insights into liquidity management emerged. It appears that some agents falsely report being out of float in order to reserve it for their loyal customers, or opt not to rebalance due to either indecisiveness as to how much to invest, or fear of being robbed or defrauded.

To add to these enduring challenges, in July last year Safaricom removed its exclusivity clause opening up their network to rival providers. Although this has a positive impact in terms of an added revenue source for agents, non-exclusivity forces them to manage multiple pools of liquidity simultaneously, and therefore can further complicate the process of rebalancing. This is especially applicable for banks whose agents are increasingly non-exclusive (74% in 2014), compared to their mobile network operator (MNO) counterparts (12%), and carry out higher value transactions (median value of $US33 per day, compared to $US22 for banks).

Poor customer recourse at the agent level

Given the negative experience customers often encounter with customer care offices and call centres, it is no surprise that they often look to agents to resolve their issues. But are agents able or willing to provide adequate service in return?

Although an impressive 89% of Kenyan agents report receiving initial training, only 29% are subsequently retrained and, therefore, may be unaware or unsure of new products and processes. Beyond training, their experience with customer call centres appears to be as dire as their customer’s.

“The biggest barrier [for agents] to expanding their business is really the fear of calling customer care when anything goes wrong, which is interesting because we would expect this to happen in countries […] where institutional setups are not yet operating optimally.” Kimathi Githachuri, Head of The Helix Institute of Digital Finance during the CGAP “Doing Digital Finance Right” event on June 29, 2015

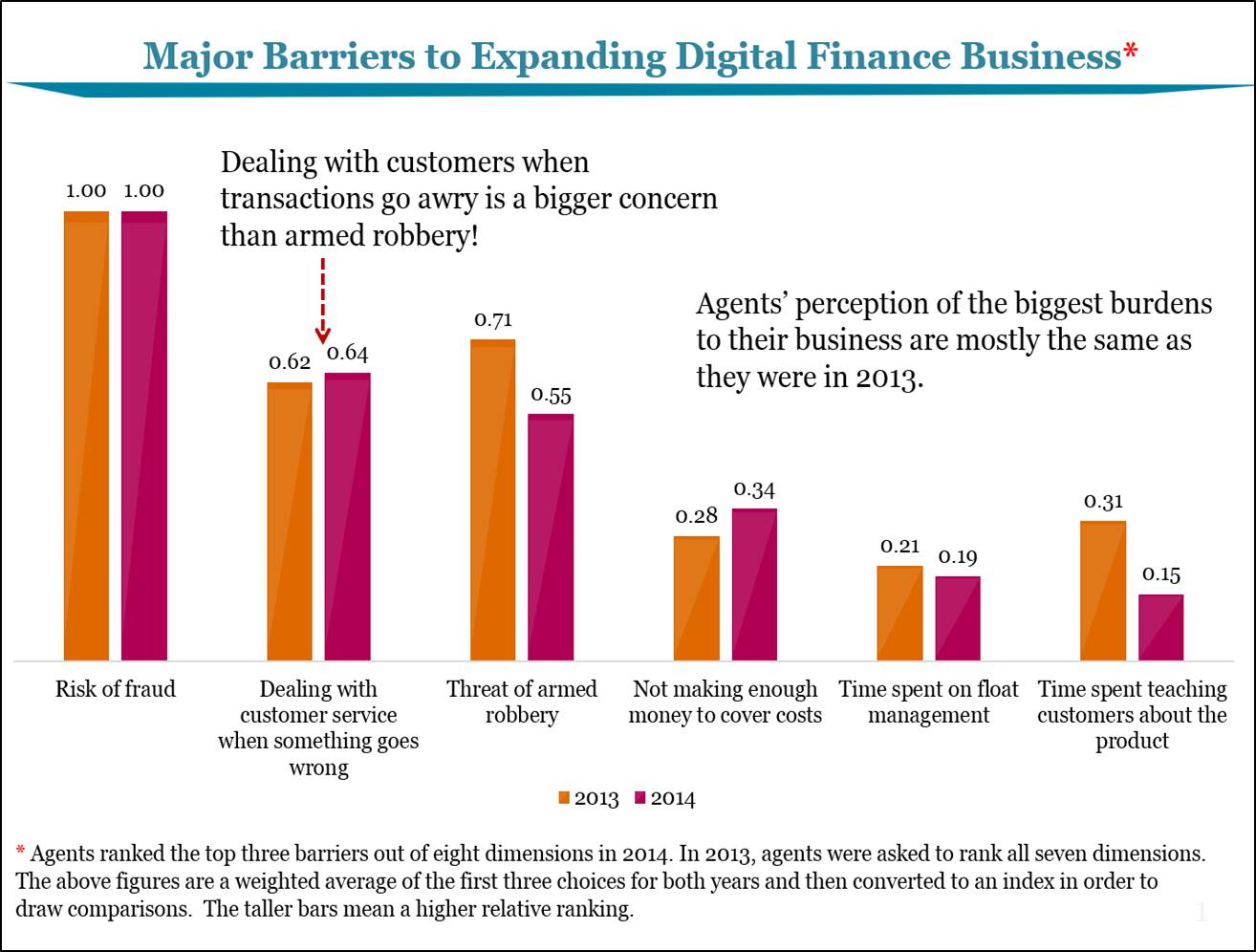

When asked to rank the major barriers to expanding their mobile money business, agents in Kenya rated ‘dealing with customer service’ second, ahead of threat of armed robbery.

Source: ‘Agent Network Accelerator Survey – Kenya Country Report 2014’

In terms of willingness, regular agents are used to selling fast-moving consumer goods (FMCG) such as cigarettes and Coca Cola, which are quick, easy transactions. They are not accustomed to spending time helping customers deal with service problems they encounter. Through sophisticated analysis of our agent data, we see direct correlations between good customer service and increased business, with the agent’s ability to answer a difficult question about a mobile money policy increasing their transaction volume by over 10%.

Banks are bringing in a greater diversity of services, beyond the popular cash-in/cash-out and bill payment products championed by MNO providers. As service offerings become more varied and complex it will become increasingly important for providers (especially banks) to identify sophisticated segments of agents that can explain these offerings and help customers deal with problems that arise.

Conclusion

Although an exciting and much needed development, the rapid growth of bank agents in Kenya comes with both its risks and rewards. Not only must banks ensure that their systems and processes develop at the same speed with which the market matures, but also that competition on the ground remains healthy. Ensuring customers are supported and protected every step of the way is a prerequisite to increased uptake and usage, and is particularly true for new and more complex products. Data from The Helix Institute of Digital Finance and MicroSave’s “A Question of Trust” study, along with CGAP’s landmark Focus Note highlight the damage these risks are doing to consumers’ trust in, and thus use of, digital finance. Those providers wishing to sprint ahead and drive healthy margins from their digital ecosystem, will need to respond accordingly.

by

by  Aug 17, 2015

Aug 17, 2015 5 min

5 min

Leave comments