Can locally-led adaptation planning extend the digital and financial inclusion frontier?

by Graham Wright

Mar 1, 2024

4 min

Can digitally enabled locally-led adaptation turbocharge locally-led adaptation strategies? Embracing tech like AI, satellites, and crowd-sourcing offers new avenues for scaling and optimizing adaptation efforts. Learn how innovations can shape the future of climate resilience in our blog.

Excluded communities

Historically, financial service providers (FSPs) have struggled to include more remote, vulnerable, and poor people into the formal economy. 1.4 billion adults worldwide still do not have a bank account.

The Findex 2021 survey reported that 76% of adults had an account at a bank or regulated institution, such as a credit union, microfinance institution (MFI), or a mobile money service provider. In developing countries, 13% of these accounts were inactive, even when we use the conservative measure that the respondent “did not use their account at all in the previous year.” Given that governments were making payments to support post-COVID-19 recovery in the year before the enumerators conducted the survey, this figure probably understates the underlying inactivity significantly.

The reasons for this exclusion are well known. They include geographical barriers, since limited distance and poor infrastructure in remote areas restrict access to services. This is compounded by economic vulnerability, as poor communities often lack the income or documentation needed to use traditional financial services. Gender disparities further impede women’s inclusion, and a lack of financial capability limits broader participation. Policy and regulatory constraints, such as restrictive policies and high compliance costs, also hinder service expansion.

These excluded people are also often stranded on the wrong side of the digital divide as a result of the lack of access to mobile phones, poor internet connectivity, and low digital literacy compounded by unsuitable user interfaces. They are also most likely to be vulnerable to climate change and have the greatest need for information and financial services to cope with climate events, recover from them, and adapt to build their resilience.

FSPs have not been willing or able to support these excluded people on commercial terms. This is unlikely to change without de-risking, and in some cases subsidies, for them to do so.

Could climate funds be a catalyst?

UNEP estimates that the climate change adaptation costs for developing countries will increase to USD 160–340 billion annually by 2030 and USD 315–565 billion by 2050, which is five to seven times higher than the USD 49 billion of global adaptation flows in 2019-2020.

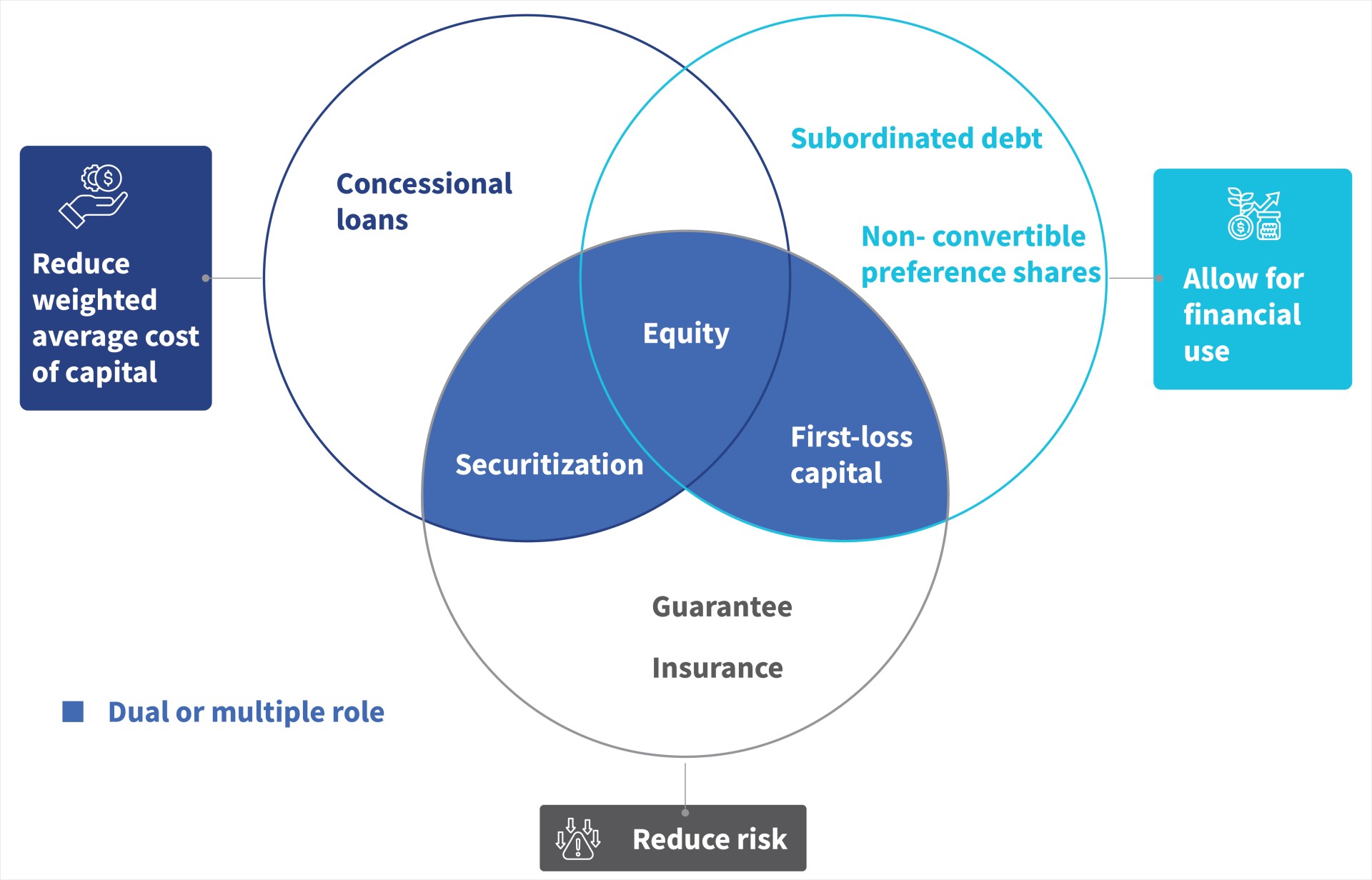

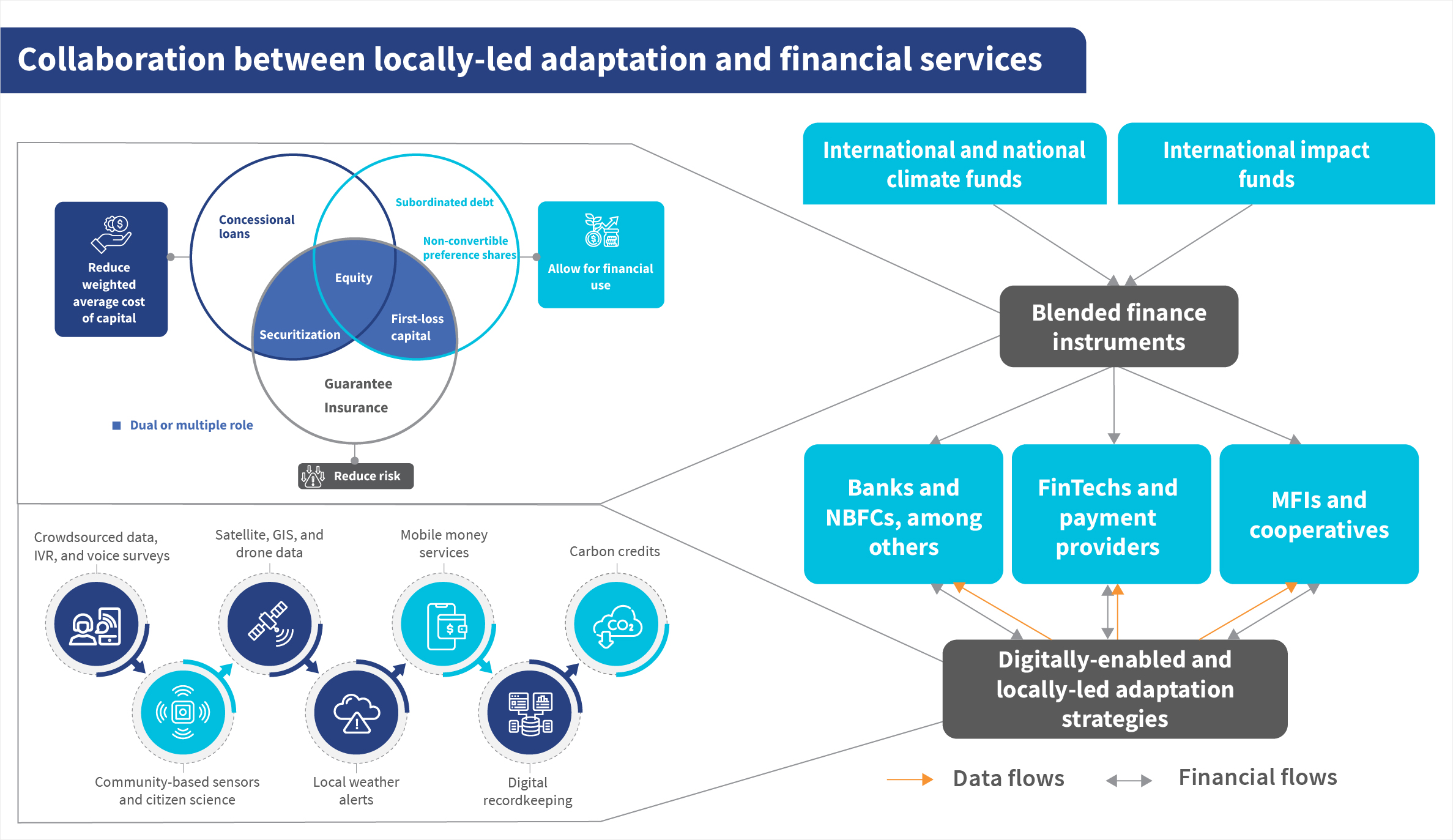

International and national funds, alongside impact funds, could use blended finance instruments to unlock public and private sector capital to address this chasm between the need for finance and its availability. Blended finance instruments can be used to reduce risk, permit capital leverage, and reduce the average weighted cost of capital. Using these instruments in preference to, or alongside, the grants that are most commonly used by many of the climate funds at present, could stretch precious adaptation funds and help bridge the chasm.

What role should blended-finance play?

Can digitally enabled locally-led adaptation turbocharge locally-led adaptation strategies?

Digitally enabled locally-led adaptation (LLA) is essential to scale and optimize locally-led adaptation strategies. It also offers the opportunity to create digital profiles and thus conduct risk analyses of these populations and their livelihoods.

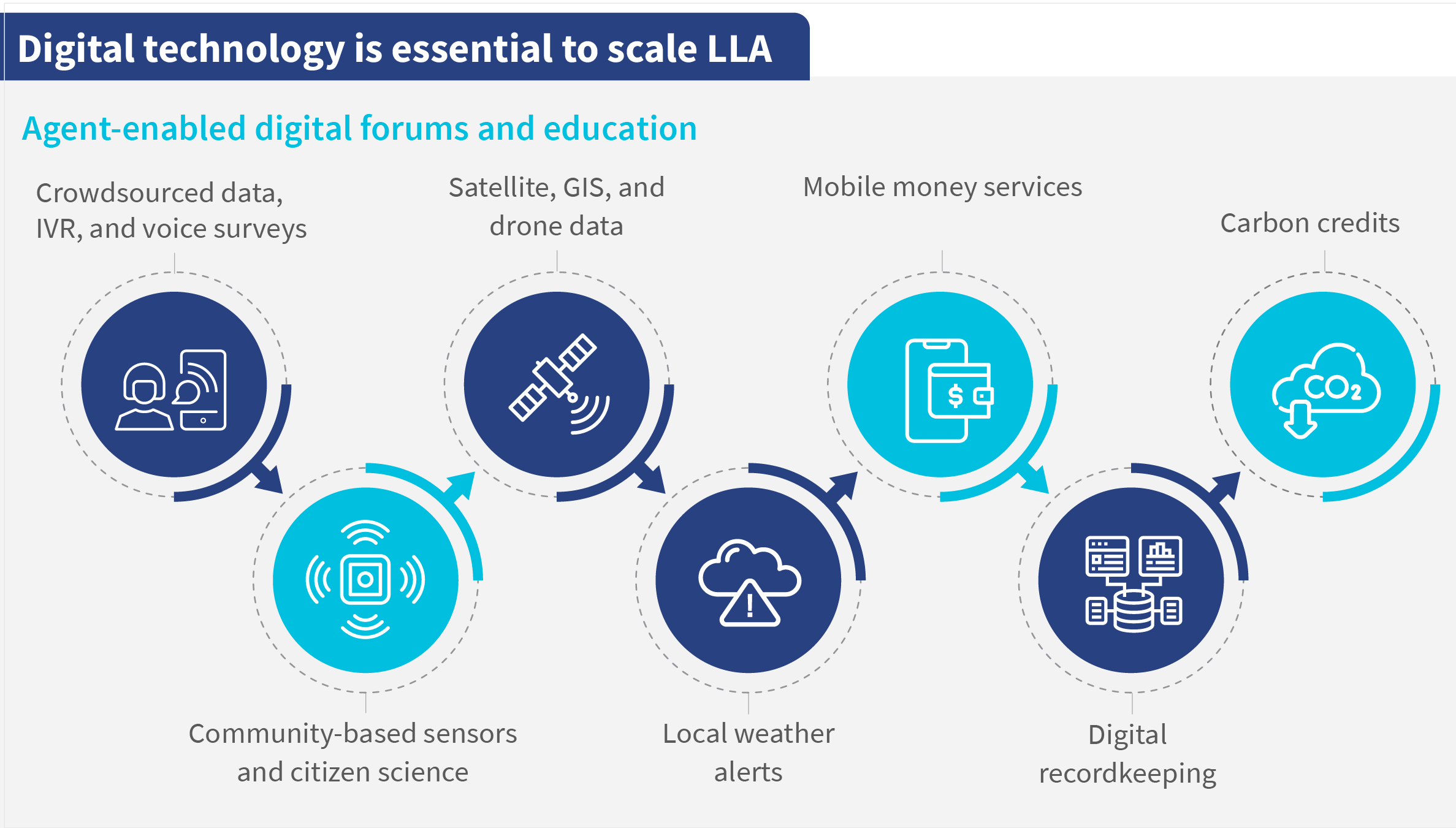

Digital technologies driven by satellites, crowd-sourcing, and AI, such as those used by CropIn, Ushahidi, and Amini, have great potential to support LLA planning and implementation. Community-based and operated sensors could collect localized climate data for analysis and planning and complement climate change predictions from GIS and machine learning models. As adaptation plans are implemented, local language weather apps, such as TomorrowNow, could provide communities with vital alerts about imminent weather changes to enable them to prepare and respond better.

These technologies can expedite and scale strategy development processes, support implementation, and enhance governance functions, such as monitoring, evaluation, and learning. Additionally, the carbon offsetting programs that could also provide some funds for adaptation often face challenges in the certification of carbon-offset activities and distribution of funds to the intended vulnerable communities. Digital platforms, such as CaVEx, present opportunities to overcome these obstacles and ensure more effective implementation and payment of benefits.

Communities can use community-based and operated sensors, satellite and drone services, and feedback platforms to report progress and challenges in real time. Mobile money services and digitally-enabled smart contracts could be used to ensure the transparent and efficient delivery of funds for adaptation projects against performance targets. Furthermore, digital payments and digital record-keeping could ensure the accountable use of resources and thus create important digital trails that facilitate credit risk appraisal and lending by formal financial service providers.

Findings from the Global Findex 2021 survey likewise reveal new opportunities to use digital payments for wages, government transfers, or the sale of agricultural goods, to drive financial inclusion and expand the use of financial services among those who already have accounts. Digitalizing some of these payments is a proven way to increase account ownership. In developing economies, 39% of adults—or 57% of those who had an account with a financial institution (excluding mobile money)—opened their first account specifically to receive a wage payment or receive money from the government.

Opportunities to facilitate locally-led adaptation strategies

Indeed, MFIs, credit unions, and other community-based FSPs and their agents are well-placed to facilitate digitally enabled LLA planning and strategy development alongside capacitated local government officials. Doing so would allow FSPs to deepen their understanding of the needs, aspirations, and behaviors of these climate-vulnerable communities, and learn how they mitigate the risks they face. This, in turn, would allow FSPs to use the funds and blended finance instruments offered by international and national climate funds and impact investors to provide financial services to these communities.

Bridging the digital divide

In addition, the use of digital technologies as part of the LLA process provides us a unique opportunity to get these populations used to digital devices and data and comfortable with them. These LLA-driven use cases provide opportunities to offer real value to these hard-to-reach communities, increase their resilience, and demonstrate the benefits of digital tools to them. Many of the most vulnerable communities comprise smallholder farmers who could benefit from digitally-enabled value chains and financial services.

Climate change, and the LLA response to it, could very well become an essential bridge across the digital divide for these farmers and others currently stranded in the analog world.

Written by

by

by  Mar 1, 2024

Mar 1, 2024 4 min

4 min

Leave comments