Blog

Closing the digital gender divide: What’s next for the digital economy?

Digital transformation has become today’s buzzword, and a focus of most countries —and Indonesia is no exception. Although the digital revolution promises to improve social and economic outcomes for women, it also comes with the risk of perpetuating patterns of gender inequality.

This year, Indonesia’s Digital Literacy Index 2021 is at 3.49, or close to a moderate stage. However, when we assessed a sample of 10,000 respondents in terms of gender, 55% of male respondents had a higher digital score above the national average. In contrast, the proportion of female respondents was only 45%.

The digital journey for women is not seamless. Several barriers keep women and girls offline, such as expensive mobile devices and data packages, lower digital skills, and restrictive social norms.

A report from the Alliance for Affordable Internet (A4AI) in 32 lower-middle-income countries reports that countries have missed out on USD 1 trillion in GDP due to women’s exclusion from the digital world. Thus, closing the digital gender gap is not just a moral cause; it is an economically crucial opportunity for women to participate in the economy.

In Indonesia, women own 61% of MSMEs. Yet only 17% of them are present on the e-commerce platforms. The effects of the pandemic urged MSMEs to access markets using digital technology to help the nation’s economy revive and grow. MSMEs must therefore seek to integrate with the digital ecosystem to survive and thrive. However, connecting MSMEs to the digital ecosystem is notoriously complex. For women, the challenges intensify.

Women experience systemic gaps, while discriminatory practices prevent women-led MSMEs from social and economic participation, and from financial and digital inclusion. Women cannot safely own or access essential digital services, skills, and resources as a fundamental right, which discourages women-led MSMEs from competing digitally in the marketplace. Additionally, they struggle to enter the digital ecosystem due to other factors, such as a lack of gender-responsive digital infrastructure, inadequate market access, and limited control and ownership of productive digital skills and assets.

What key actions can support the effort to close the digital gender gap in Indonesia?

First, the flagship National Strategy of Women’s Financial Inclusion, which targets around 83 million women, can serve as a strategic entry point. However, it must be implemented widely and re-evaluated to target the right audience, connect women to digital financial services, and create an enabling environment for women-led MSMEs.

Second, clearly stating the figures in the Gender Responsive Planning and Budgeting (GRPB) should be mainstreamed to all line ministries and assessed regularly by the Ministry of Development Planning, the Ministry of Women Empowerment and Child Protection, the Ministry of Finance, and the Ministry of Home Affairs to maintain implementation quality at national and regional levels.

Third, the government can provide a support system to empower more women in STEM and ICT through affordable access and consistent policies in partnership with stakeholders. A study by ILO across the ASEAN region reveals women’s participation in computer programming, consultancy, and related activities in Indonesia stands at only 21%.

Fourth, enhancing easy and safe access to digital skills through gender-responsive entrepreneurship training and program can help the women-led MSMEs compete in the fierce digital marketplace.

Most recommendations above were discussed in detail at the G20 Ministerial Conference on Women’s Empowerment (MCWE) in Bali last August 2022. The G20 country members highlighted the need for collaboration between economies to close the digital gender gap. Participants agreed that member countries should open more opportunities for women to participate in STEM and digital sectors and build their digital resilience.

The Conference agreed that women’s participation in the digital economy needs serious attention, considering the enormous cost of digital exclusion to the economy. As the host of this year’s presidency, Indonesia must now urgently push the women’s empowerment and gender mainstreaming agendas.

Besides, the Women20 and G20 Empower Initiative members also highlighted the urgency of enabling women and girls’ skills in digital technology and scaling up the foundation to support women-owned businesses through inclusive ICT and economic recovery policies and programs.

Yet, the outputs of the G20 MCWE 2022 to the G20 Leaders leaves stakeholders, such as the Ministry of Women Empowerment and Child Protection, think tanks, academia, and the private sector, with much to advocate for. Only through such advocacy can gender issues be mainstreamed and women be empowered to enjoy unrestricted access to the digital economy. Because a digital economy that does not include women adequately cannot scale to reach its full capacity.

Climate change and river erosion—what can we learn from the past?

Chars and river erosion

Chars are riverine sand bars of two types: attached chars and island chars (Roy et al., 2015). Madbor Char is, or was, an attached char linked to the mainland under normal river flow conditions. However, as Ahmed Zoheeer, et al., 2021 note, “during the dry seasons, attached chars can be accessed without crossing a river channel. During the floods, many attached floods become island chars.”

So perhaps it was no surprise that in 1993, river erosion prevailed, and the waters of the Padma engorged my brother-in-law’s country home and many of the surrounding fields. The process happened slowly, painfully, and inexorably over three months between August and October until the entire edifice was lost forever. Many poorer families living in Madbor Char were rendered landless and destitute.

This reminds us that while we can safely assume that climate change is exacerbating and accelerating rapid-onset events in the Gangetic delta, these forces have been inherent in the geography for millennia.

The consequences

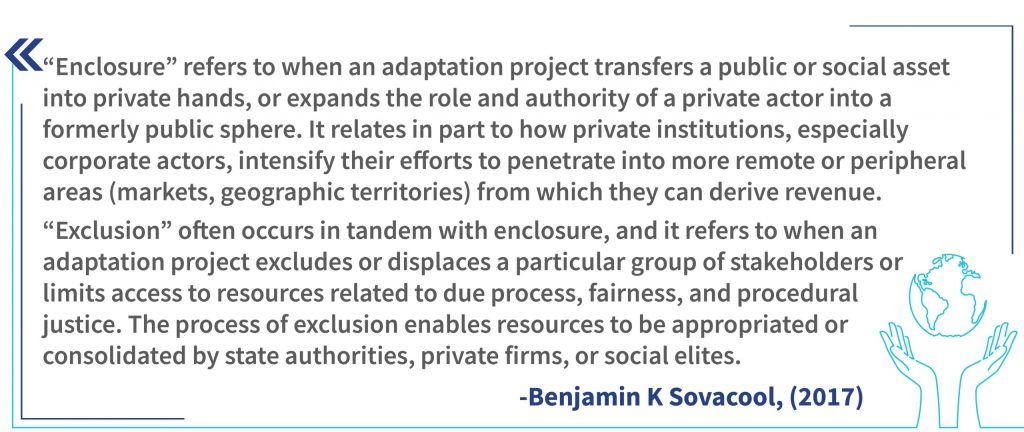

The impact on vulnerable families is devastating. Sovacool & Linnér, (2015) tell of “Abul Kalam, who used to be a professional fisher, is now a rickshaw puller living with his family of eight in a temporary thatched shack next to the canal of a fishery ghat (landing center for boats).” He migrated to Chittagong city in 2008 after he lost three acres of land due to erosion brought about by the Meghna. He says, “I shifted house three times due to erosion. My family members lived on other land after losing assets. Erosion changes everything; our home, livelihood and the society as well. River erosion is the curse for us”.

This photo essay highlights the process and experience of affected families—many of whom are forced to migrate to cities in quest of work.

And when families are made destitute, women bear much of the burden. As Tanzina Dilshada et al., (2017) note, “when a family becomes poor it affects women in those families in many ways. If there is food shortage, women take less food, which affects their health. It affects girls’ education and increases threat of early marriage, and encourages the dowry system.”

Lessons

So what can we learn from how families have responded to river erosion of land and livelihoods?

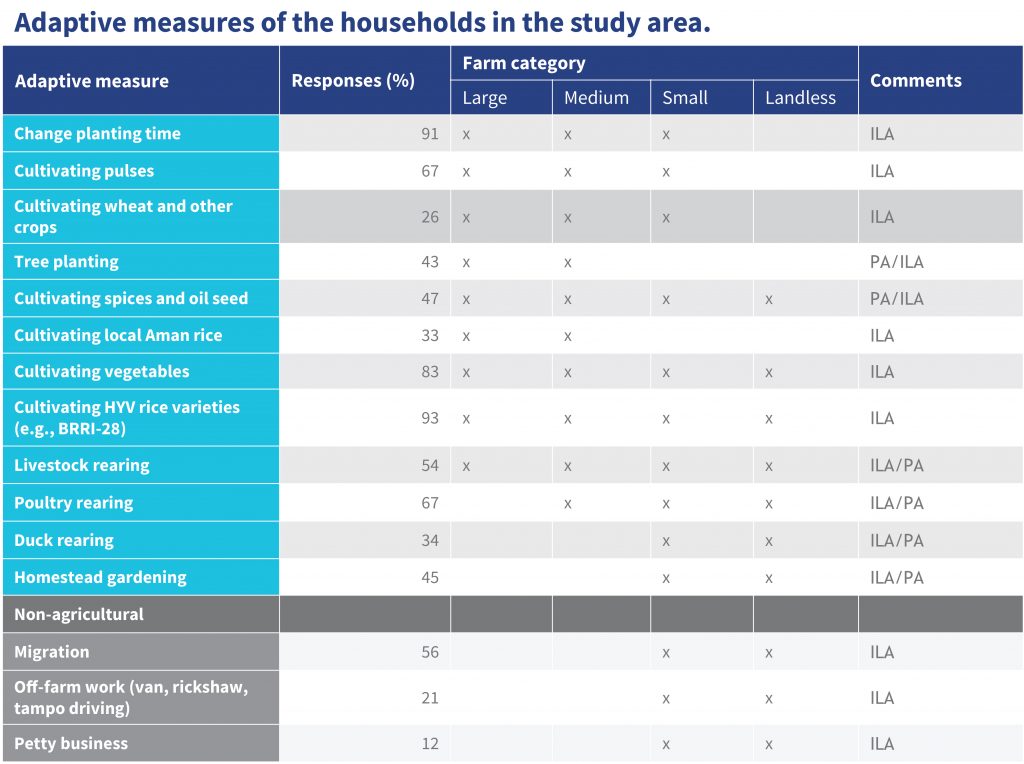

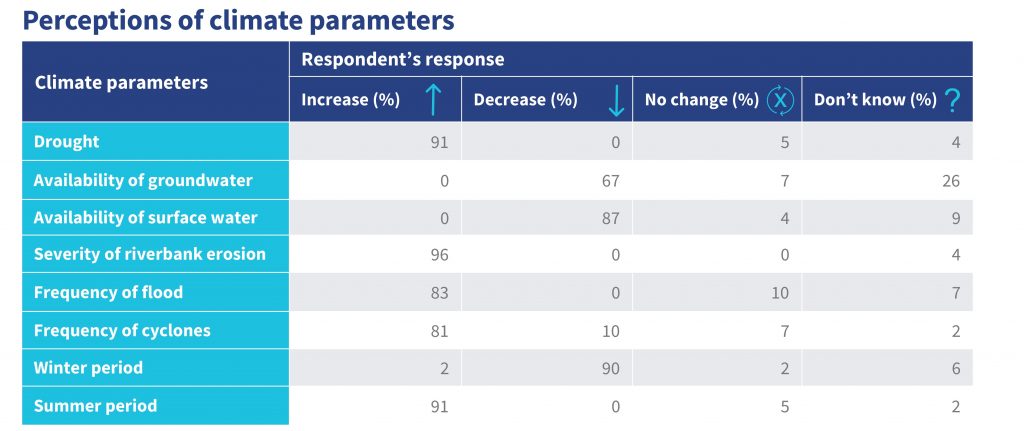

First, the people of Bangladesh recognize the impacts of climate change and are responding to them. As Table 1 below shows, the impacts are more multi-dimensional than just increased river erosion. More instances of extreme weather events due to climate change mean that both flooding and summer droughts have increased alongside increased river erosion. Indeed, these extremes are amplifying the erosion processes.

“The study revealed that despite the difficulties of riverbank erosion and other climate change issues, all of the resource-poor households were attempting to sustain and to improve their livelihood through a range of adaptation strategies” Alam et al., (2017).

Perhaps unsurprisingly, the adaptation strategies vary according to the affluence or farm size of the respondents. Almost all farmers had changed both the crops and varieties of rice they plant and the times they plant them to try to manage the changing weather patterns. Many small and landless farmers have diversified into livestock and poultry rearing, often under the guidance of the government or NGOs. And more than half of these poorer households have members who have migrated to cities to earn additional income.

River erosion and the delta dynamics also create new chars, and thus opportunities to live on and farm the rich soil of these sandbars. However, the more affluent households in the area often seize the most viable and least marginal of these opportunities.

My brother-in-law’s family migrated to Dhaka and rebuilt relatively comfortable lives in the capital. The Padma River had created another char a few miles from where Madbor Char once stood. More affluent and influential families in the area soon enclosed and occupied the new char, to the exclusion of the poorer ones. Yet many of the vulnerable families from Madbor Char were left landless, destitute, and struggling to rebuild their lives from those fateful months in 1993.

Bangladesh and climate change—lessons from the frontline

A country at risk

Fifteen percent of Bangladesh’s 162 million people live just one meter or less above high tide (Richard, 2007), and annual floods inundate 20% to 70% of the country each year (Mirza, 2002).

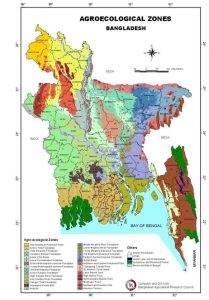

To the casual observer, much of the country appears to be similar: flat, low-lying, lush, and extraordinarily beautiful. But in reality, Bangladesh is a rich tapestry of 30 agroecological zones, each with unique opportunities and challenges. Climate change exacerbates diverse problems—many of which have plagued Bangladesh for millennia. Climate change has prolonged droughts in the northwest and pluvial floods in the northeast. Fluvial floods and river erosion are more common and extreme in the country’s center. Further, the salination of soil and erosion in the southwest due to the rising sea level is also a growing problem.

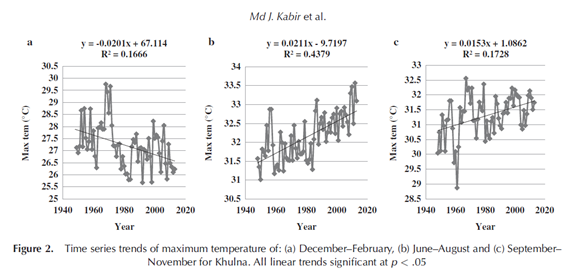

And the people are aware of it Farmers are aware of the changing weather, even if many are unaware of “climate change” or what it means. They correctly identify increased extremes in temperatures at the height of the summer and depth of the winter. They note that the rains are often late, heavier, and unevenly spread over the months when they are expected. Even though they are subject to the recency effect when discussing cyclones, men’s and women’s mental maps of the changes in the weather on which they depend are remarkably consistent with those recorded by sophisticated weather stations across the country.

For example, farmers’ perceptions of the rise in summer temperature, decline in annual rainfall, more erratic rainfall, and increased frequency of rainfall were consistent with trends found in the Khulna Climate Station data. Also, their perception of increased rainfall in the post-wet-season months and the intensity of extreme weather events were consistent with the station’s data.

Source: Farmers’ perceptions of and responses to environmental change in southwest coastal Bangladesh, Kabir et al., 2017

However, these time series of maximum temperature charts hide the larger problem of significant fluctuations in the intensity of rains and sharp periods of drought within the different months—it is this variability that causes most of the damage to crops and livestock. Farmers in Khulna District note that the rainfall pattern has changed substantially over the past two decades. The number of rainy days and the total rainfall have declined, but the incidence of drought during the three main cropping seasons has increased. (Kabir et al., 2017).

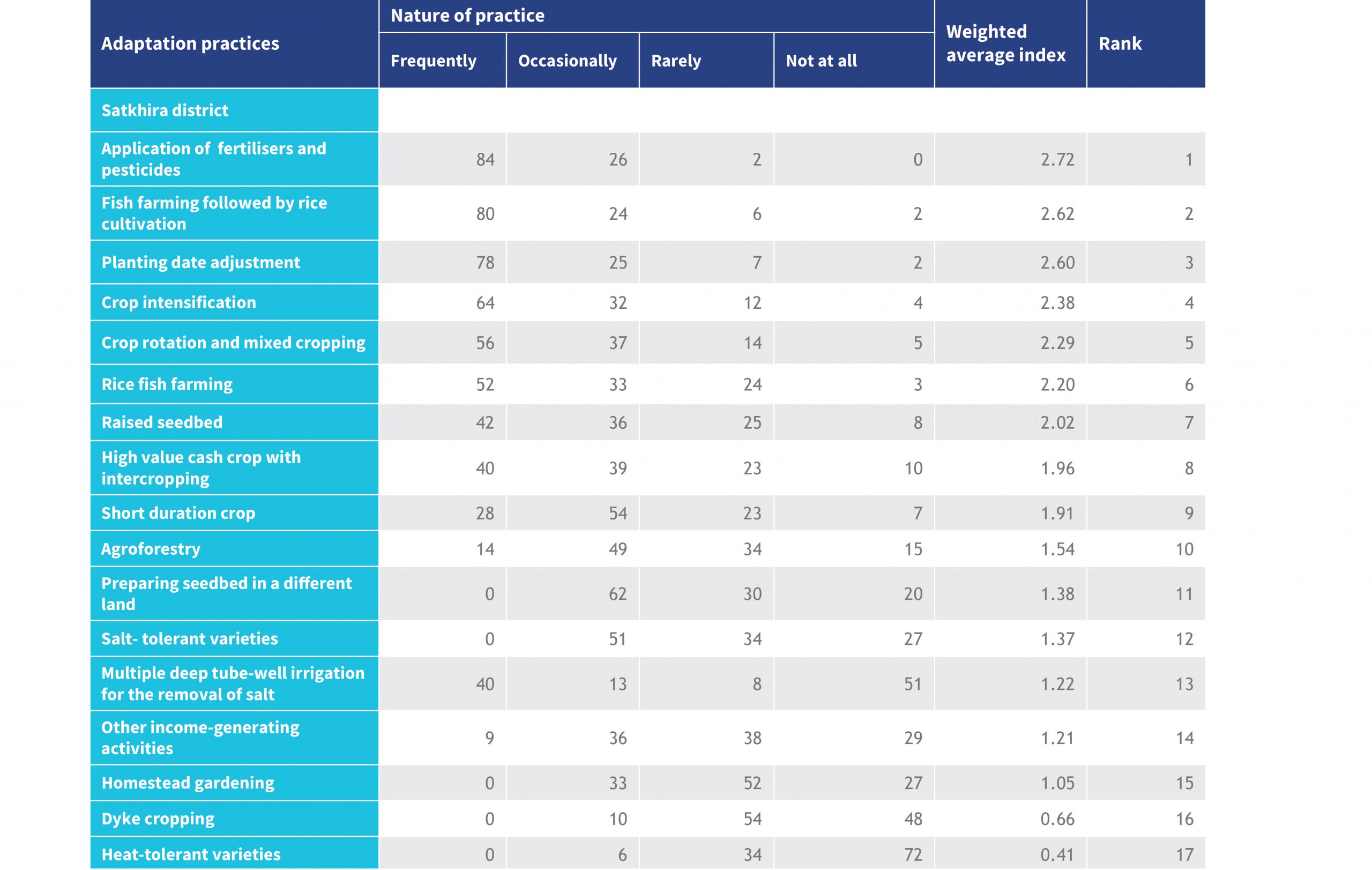

Table 5: Rank order and index of farmers’ perceptions of climate change on crop production in Satkhira

For example, farmers in Satkhira District ranked the impact of climate change on crop production, as shown in Table 5 (Khan et al., 2022). Inevitably, these impacts vary across agroecological zones, but many are common—only their position on the rank varies.

Women are particularly badly affected

Bangladeshi women are particularly vulnerable to climate change. They typically have limited, low-productivity livelihood assets and options, such as small agriculture, vegetable gardening around the homestead, poultry and livestock, and small business. Climate change affects these livelihoods severely due to floods, cyclones, tidal surge, drought, and salinity. These events impact their food security, drinking water, sanitation, and health. In some extreme cases, entire families have to migrate to cities for employment. (BCAS unpublished “Vulnerability of Women and Poor to Climate Change: Gender Responsive Adaptation in Bangladesh”).

While this is true, Evertsen, Kathinka (2022) suggests that we should not simply see women as the key drivers of adaptation. To see “… success stories of women transformed from victims to agents of change who need to be brought in to increase the adaptive capacity of their communities”, places the responsibility for, and burden of, adaptation on their shoulders. This creates the “risk that women will be used as instruments … in climate change adaptation projects while overlooking the root causes of gendered vulnerabilities”.

“We are talking about the alternative livelihood, we are trying to empower the women to have some employment.…but actually, this is an additional responsibility for her. But we are never thinking about that.

Sarah White has noted how ‘women’s entry into the waged labour market does not typically mean they relinquish responsibilities for housework’ (White, 2017, p. 256). Thus, the recognition of women’s contributions ‘appears to have been achieved at the expense of appreciation of their unpaid workload within the household’ (Kabeer, 1994, p. 26), resulting in a ‘feminization of responsibility’ (Chant, 2008).”

— Evertsen, Kathinka (2022)

Active not passive

Women and farmers in Bangladesh are by no means passive in the face of the climate crisis engulfing them. On the contrary, they are responding with the creative resilience with which they have natural disasters for decades now. Table 7 from Khan et al. 2022 highlights how farmers have adapted to climate change by increasing inputs, introducing fish and shrimp farming, changing the timing of agricultural cycles, and diversifying crops to align with the changed weather conditions.

Table 7: Ranking of adaptation measures practised by the households in the study area

Further, farmers have raised their seed beds to higher levels to avoid flood waters and use deep tube well irrigation pumps to flush out the salt from their fields. Alam et al., (2017) also identified 15 adaptation strategies based on affected people’s long-term knowledge and perceptions of climate change and “planned adaptation” supported by the government and nongovernmental organizations (NGOs). Perhaps unsurprisingly, these adaptation strategies vary according to the affluence or farm size of the respondents. In particular, access to credit affects the ability of households to adapt to climate change—especially during rapid onset events, such as floods or river erosion.

But struggling for resources to adapt

Fenton, Adrian et al., (2016) notes that “Even if it does facilitate adaptation, credit limits imposed by MFIs may limit its role to incremental adaptations. Incremental adaptations facilitated by access to microfinance were not sufficient to offset the ongoing effects of flooding on agriculture, the most important household income generating activity.” Moreover, most microfinance loans were too small to allow farmers to transform their livelihoods by setting up shrimp farms or sending a family member abroad to earn and remit income home.

Most transformational adaptations required access to bank credit, which is only available to the most affluent households. Lack of access to credit restricts the ability of poorer households to adapt effectively. As a result, they use smaller loans, often from informal moneylenders, to cope. Fenton, Adrian et al., (2016) also found evidence that “microfinance can lead to maladaptation when used in non-profit generating activities as these activities do not produce income streams to help repay associated costs. Almost a fifth of all loans were obtained for repaying existing loans.” As one household interviewee said, “I can start a business; however, the interest charged would be more than the profit. If I go [abroad], that amount of money I would be able to make will be sufficient to repay.”

Multidimensional maladaptation

Evidence suggests that another type of maladaptation is a growing problem. Short-term solutions, such as chemical fertilizers and pesticides in response to declining soil health or the growth of pests, are turning out to be unsustainable. A farmer cited in Misra, 2016 said, “Our land has become sterile as we continue to use chemicals. Earlier, we could harvest a decent amount of crops without applying any fertilisers, but these days you wouldn’t be able to harvest anything without fertilisers. Twenty years back, we applied only 10 kilograms of urea on a bigha (33 decimal) of land. Nowadays, we apply 40–60 kilograms. Now, you tell me whether the land has gained productivity or has lost it?.” This problem is not unique to Bangladesh. MSC saw similar issues in its recent work on the impact of smallholder farmers in Bihar.

Conclusion

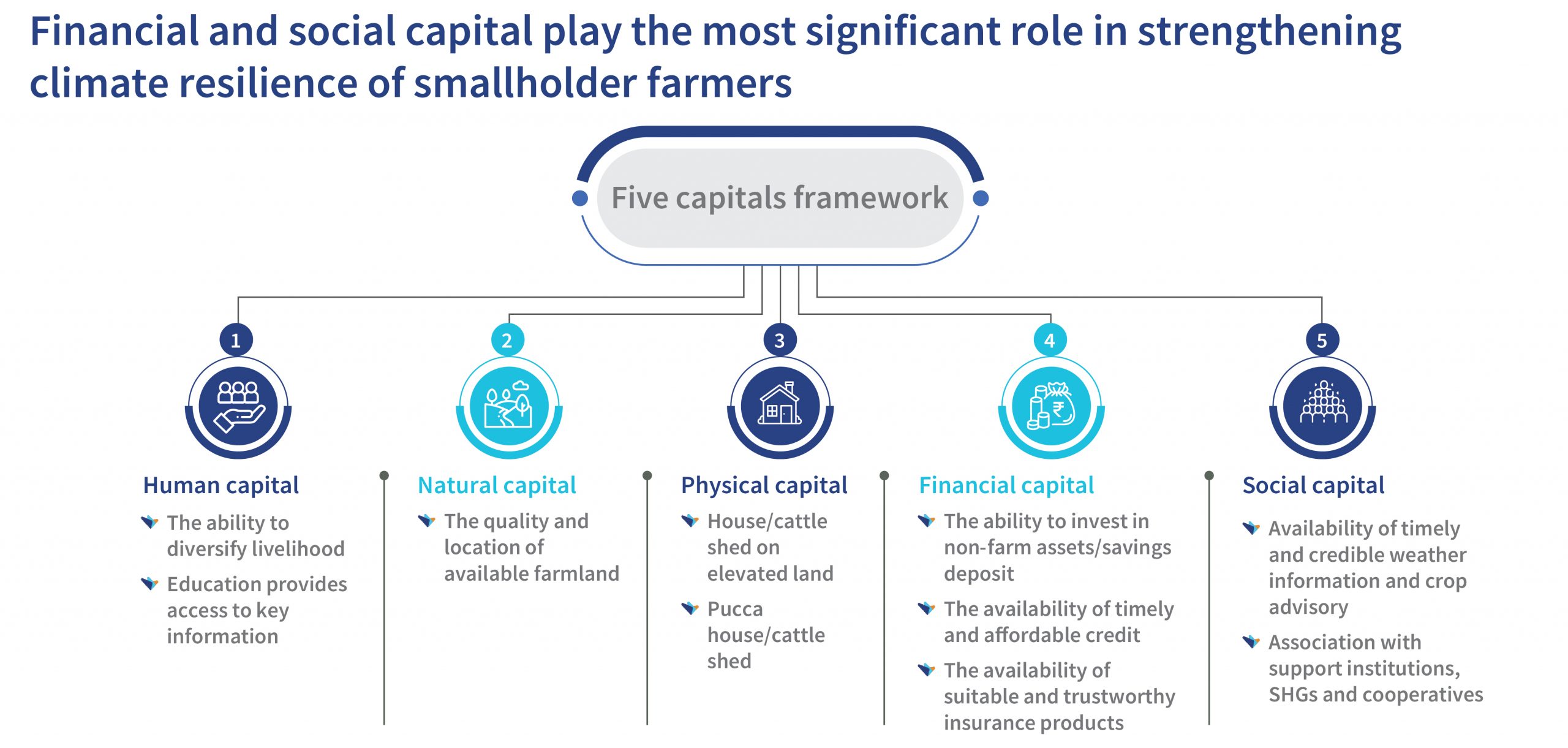

Bangladesh is on the front line of climate change, which presents a clear threat to millions of people in the country—and the world. The dynamics of the dangers they face vary across seasons, agroecological zones, socioeconomic status, gender, and their endowment of the five capitals: human, natural, physical, financial, and social (see Five capitals framework). We need to deepen our collective understanding of these factors and listen carefully to the voices of those already affected by the climate emergency.

The impact of climate change on farmers in Bihar and how farmer producer organizations can help them adapt

“Irregular availability of water is going to be the biggest hazard in future. In case of increased water supply, the piedmont zone and river lowlands are threatened by erosion and sedimentation while in case of decreased water supply, the upland surface is endangered by salinization, desertification, and drying-up of aquifers. Decline in food production will be the major problem.” – H. Saini Climate Change and its Future Impact on the Indo-Gangetic Plain (IGP), Environmental Science, 2008

“By 2050, variability in growing conditions due to climate change is projected to lower crop yields by 10 to 40 percent and total crop failure will become more common.” – Julie Mollins, Landscape, 2018

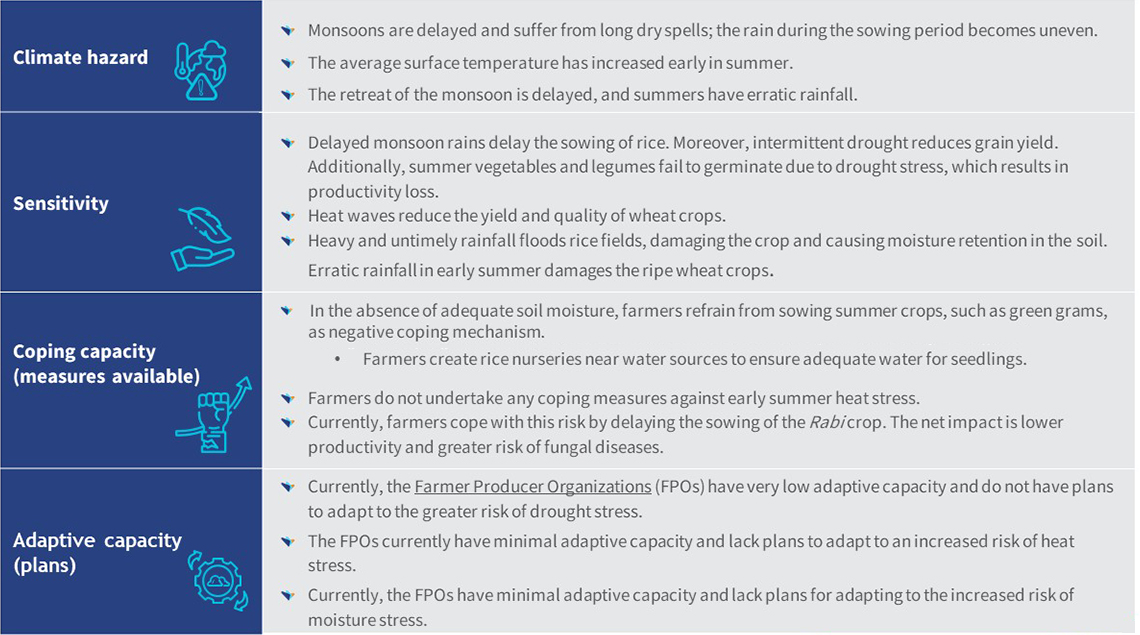

Buxar district lies on the south bank of the Ganges River between Varanasi and Patna. Droughts and unseasonal rainfall are critical risks to agricultural productivity in the district. And these risks are growing … rapidly. We cannot see these variations in weather as anything but the impact of climate change. If these are the early signs, the implications for the Gangetic Plain in the coming decades are deeply worrying.

“The weather is so variable—we do not know what to do. When we expect rain, we get none; and then suddenly, we get so much rain that all our crops are washed away. This is getting worse, and we are left helpless. We can no longer afford the fertilizer and pesticides we need in the seasons after a bad harvest. We are forced to purchase these in credit.” – Rice and wheat farmer in Buxar.

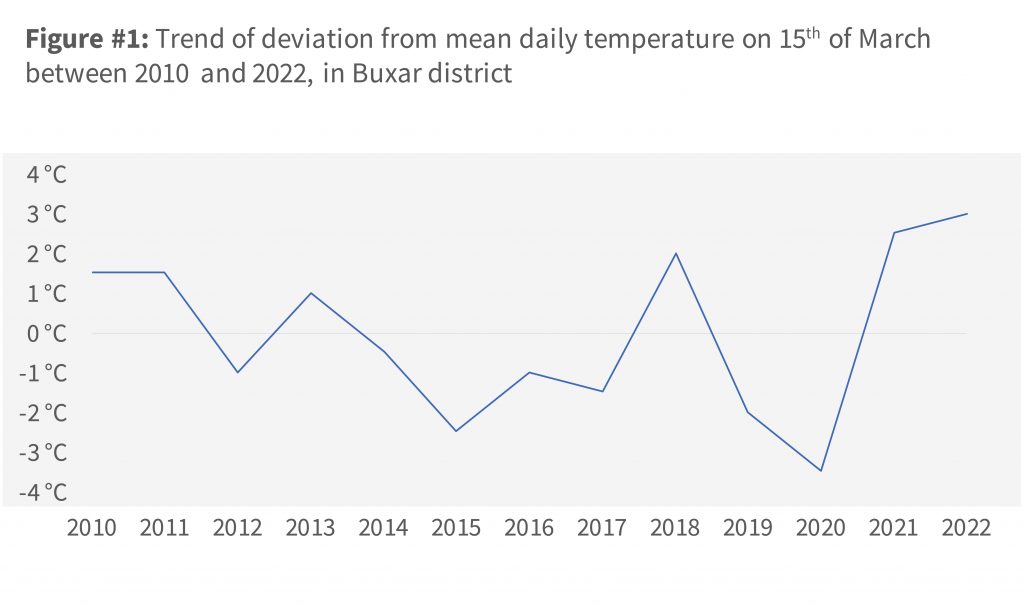

The spring temperature in the district is becoming warmer, and the variations are becoming larger.

- The daily mean temperature in the spring season (see Figure 1) has experienced a positive deviation in six of the past 13 years.

- In the past two years, the positive deviation in the mean daily has been higher than previously observed positive deviations.

- In the past two years, the district has faced intense heat waves in March, resulting in shriveled the growing wheat and thus, reduced harvest yields.

Furthermore, rainfall has become irregular in the past two decades.

- Between 1989 and 2018, the June rainfall in Buxar was highly variable (coefficient of variation = 92.4%).

- In the same period, the July-October monsoon rainfall in Buxar was also highly variable (coefficient of variation = 30.4%).

“Rains have become very irregular. When the rains start, we sow paddy. If we have a long dry period afterwards, the entire crop dries up due to insufficient water availability. We have to replant again. This phenomenon is becoming more frequent.” – Rice farmer from Buxar

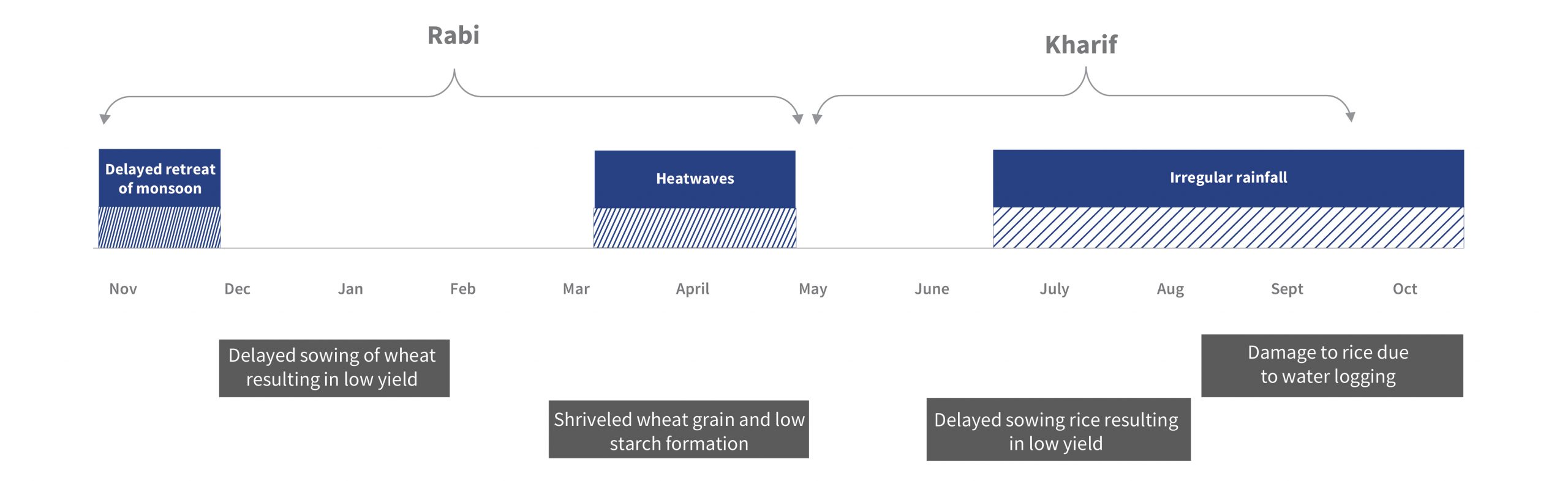

Figure 2 highlights how these slow-onset climate-change stresses affect farmers and their productivity over the year.

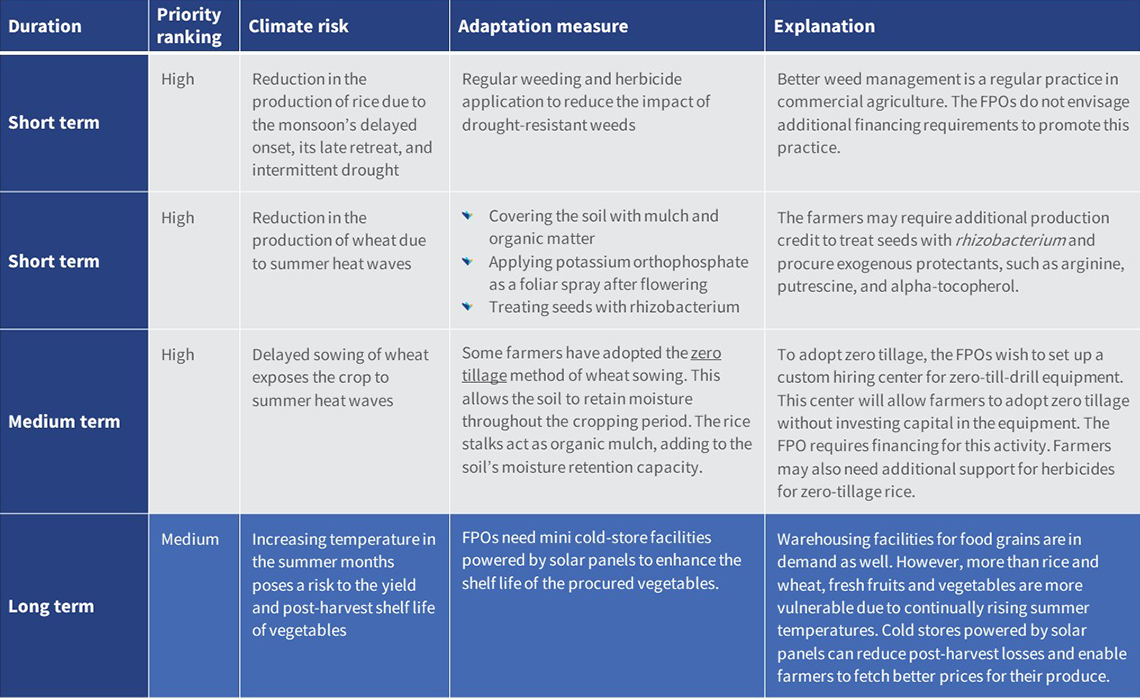

Table 1 below highlights the impact of these significant shifts in climate in Buxar. Similar impacts are likely to be replicated across much of the Indo-Gangetic plains, home to 900 million people or one-eighth of the world’s population.

In Buxar, farmers are struggling to cope with the changing conditions and adapt to them (see Table 2 below). Yet, significant annual variation in rainfall and temperature further erodes farmers’ adaptive capacities (see Figure 1 above). In some cases, farmers’ coping mechanisms risk maladaptation. For example, if farmers are compelled to delay sowing of the Rabi season crop, they risk reducing the yield, and the crop becomes prone to fungal disease.

“The only solution we have to the rainfall variability is to delay the sowing of crops. We are not aware of any other solutions to this situation.” – Rice and wheat farmer from Buxar

Farmer Producers Organizations (FPOs) are yet to spearhead collective action to build resilience to climate change impacts, but they could be the key to a more effective response.

“FPOs can mobilize resources to provide suitable tools and infrastructure to fight variations in the climate.” – FPO member in Buxar

So what should farmers and FPOs do?

FPOs should seek to play a central role to promote and facilitate farmers’ adaptation to climate change. In the short run, FPOs could serve as knowledge and communication centers to drive better climate-resilient practices among their members and serve as conduits for credit for farmers. Farmers can use such credit support to finance farm inputs and drive the adoption of climate-resilient agricultural practices to protect against multiple shocks and stresses. In the medium and long term, FPOs will need to play a more prominent role to hire farm equipment and emerge as aggregation and cold-storage centers.

Proposed solutions to many problems arising from climate change are already available among the local scientific community, such as universities and state-owned research establishments like Krishi Vigyan Kendras (KVKs). Table 2 describes examples of the solutions recommended by these institutions.

However, farmers are yet to adopt these solutions due to the:

- Lack of awareness and technical knowhow, particularly of new techniques like zero tillage;

- Lack of access to appropriate financial services;

- Inertia or status quo bias as current practices have been used for generations;

- Mistrust of new ideas.

“These farming practices have been in our family for generations—we cannot take the risk of trying new ideas. We have heard of so many people trying new things and failing. We feel what we do is right for our farms.” – Rice farmer from Buxar

FPOs can work as a platform for information and training on these new solutions, develop new business models (such as renting out tools), and demonstrate success stories. FPOs need to be adequately incentivized to empower their members to respond to climate change.

“It is in the FPO’s own interest to support its member farmers through information, training, and access to new technologies to meet the challenge of climate change.” – Director of Ravidas Baba Farmers Producer Company Limited, Buxar.

Seven factors that determine the resilience and adaptive ability of smallholder farmers in Bihar

Our previous blogs examined the impact of climate change on smallholder farmers in India’s Bihar state and their coping strategies. We also looked at the traits of resilient and vulnerable smallholder farmers. These blogs highlighted the increasing vulnerability of these farmers to fluvial and pluvial flooding and looked at their struggles to adapt to the changing climate and weather patterns.

This blog extracts the seven factors critical to enabling resilience and adaptive strategies among smallholder farmers in the flood-prone state.

- The quality of available farmland:

The topography of the farmland and the availability of irrigation sources determine its soil quality and productivity. For example, low-lying lands are likely to remain waterlogged for longer, which leaches nutrients from the topsoil, particularly when the flooding is pluvial. Leaching gradually deteriorates the topsoil’s fertility. Similarly, farmlands located near river banks experience inundation during fluvial flooding but they also benefit from nutrient-enriched silts deposited by the river.

Farmers’ natural capital governs their ability to remain resilient against weather-related shocks, determined by the following metrics:

- Irrigated as against rain-fed lands;

- Low-lying as against elevated lands;

- Lands adjacent to river banks as against lands far away from river banks.

- Association with supporting institutions and cooperatives:

Our research found that female smallholder farmers who are members of the self-help groups (SHGs) formed under the JEEViKA program receive a range of support from the program. Such support includes information and advisory on farming practices, weather alerts, financial inclusion programs, livelihood diversification programs, and marketing assistance. The female members associated with JEEViKA appeared more confident in using innovative cultivation methods, improved variety of seeds, and new crops, among other areas.

Agriculture scientists of the National Agricultural Research System play a vital role in farmers’ climate resilience as they provide crucial advisory services through the Krishi Vigyan Kendra Knowledge Network. Therefore, association with supporting institutions such as cooperatives, producer organizations, and NGOs strengthen the farmers’ capability to adapt to a changing climate.

- Availability of timely and credible weather information and crop advisory:

In a related point, critical for male farmers and women not enrolled in the JEEViKA program, we learned that smallholder farmers have access to weather-related information for free. The Department of Agriculture Meteorology of the Government of Bihar has the infrastructure needed to provide the information. In addition to weather information, local agriculture advisory centers provide credible crop production and marketing advisory services.

- The ability to diversify their livelihood:

We found most young people are migrating to cities to work in the non-farm sectors. Respondents noted that an increase in the number of CICO agents in the villages has improved the ease and experience of cashing out these remittances and government benefits. We found that households whose migrant members remit money built pucca houses on elevated lands. Smallholder farmers in the farm sector diversify their income by cultivating vegetables and other cash crops. They also rear livestock. Over the years, farmers have diversified their income sources to mitigate the risk of crop failure due to adverse weather events. This diversification is a crucial strategy and offers a form of insurance against the changing and increasingly disruptive weather patterns.

- The ability to invest in non-farming assets:

While smallholder farmers recognize the importance of diversification, including into non-farm enterprises, they fail to save their income to invest in non-farming assets. Most of them reinvest what little surplus income they have in agriculture. However, during significant weather events, smallholders use their savings for consumption, which often compels them to borrow from informal sources to invest in agriculture for the following season.

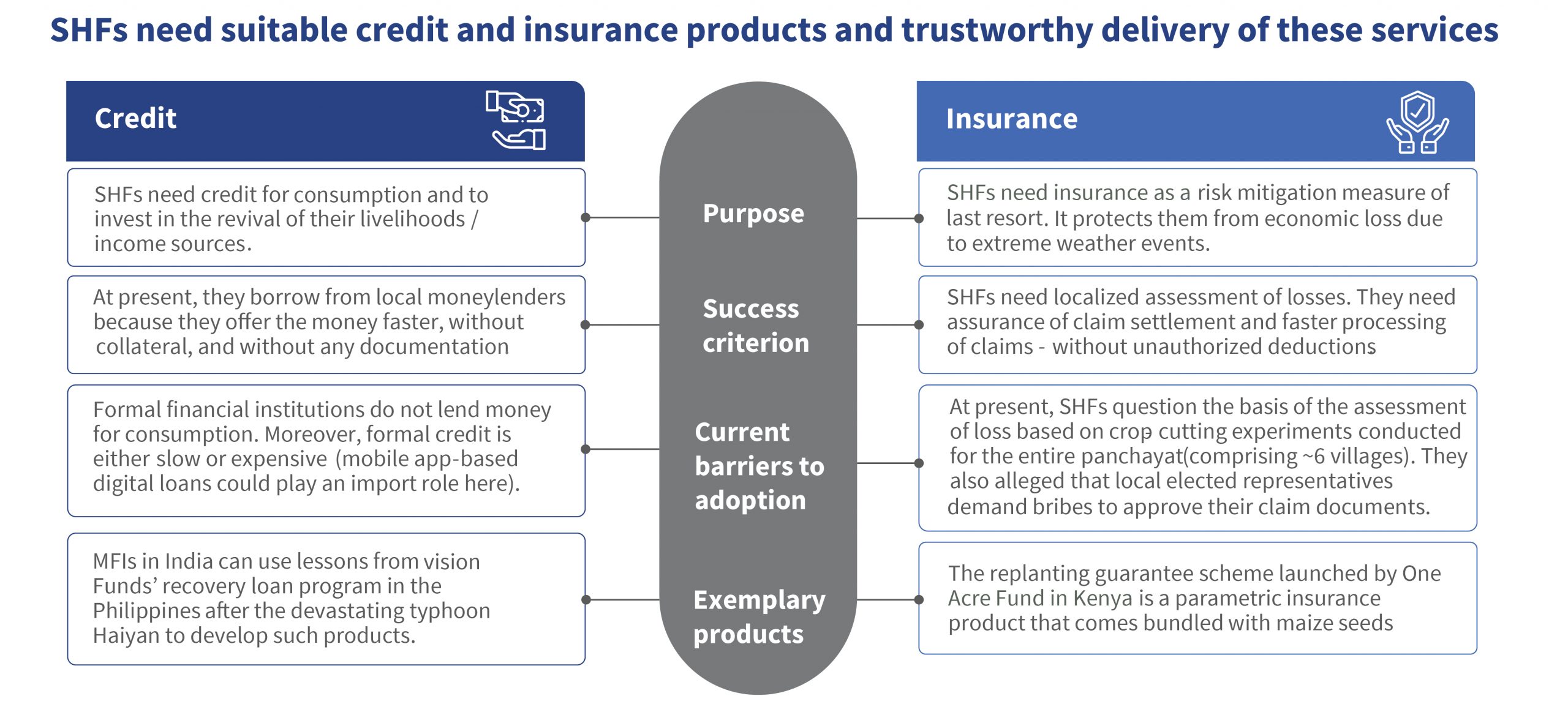

- The availability of timely and affordable credit:

As noted above, smallholder farmers often rely on borrowing to revive their livelihoods after a major weather event. They fall back on informal credit because it is accessible and timely. No other institutions lend for economic recovery, compelling smallholders to resort to informal credit. However, the JEEViKA program is a major provider of loans through its SHG networks. While the SHG network suffers from lengthy credit delivery systems and processes, it has significantly enhanced farmers’ income and ability to access credit. Therefore, in the absence of insurance, a key factor of climate resilience is the availability of timely and affordable credit to reconstruct and revive livelihoods—which are ideally diversified.

- The availability of suitable and trustworthy insurance products:

Smallholder farmers understand that insurance can help them recover from the economic impact of weather events. However, they stated that lodging claims is a tedious process and typically involves bribing local officials—up to 20% of the amount claimed. Moreover, farmers feel insurance companies should assess damages at the individual farm level. However, insurance companies currently measure the productivity loss of an entire cluster of villages—a panchayat—to determine the extent of damages they should pay to each insured farmer. Therefore, an effective and trustworthy insurance product could enable the uptake of insurance products designed to protect farmers against major perils and reduce their dependence on informal moneylenders.

The graphic below highlights the critical success factors for credit and insurance products that could bolster the resilience of smallholder farmers in Bihar.

The DFID Five Capitals Framework provides a concise way to summarize the drivers of smallholder farmer resilience and climate adaptation in Bihar. Clearly, the key determinants are the quality and location of farmland owned and the ability of farmers to diversify their farm and non-farm revenue streams. However, this framework highlights the importance of information, extension, and other services delivered by government and non-government actors in the ecosystem and the catalytic and protective role that well-designed financial services could play.