A transformation is underway in rural Indonesia. Women’s cooperatives have entered the agent business, defied social norms, and paved the way for financial empowerment for cooperative members and the broader women’s community. MSC partnered with PEKKA and BRI to support the digital transformation of three women’s cooperative agents in Tangerang, Karawang, and Bantul through the Women Digital Ambassador (WDA) project.

This blog is the third under the WDA project. The first assessed whether women’s cooperatives are ready for digital transformation. The second blog analyzed the transactions women agents conducted and the income they derived. This blog uses a gender-focused approach to highlight ways to address women’s diverse challenges in the agent business and thus increase their client base and income. We also emphasize the significance of female agents as they improve their community’s reception toward banking services and suggest strategies to expand their presence in rural Indonesia.

An examination of female agents’ onboarding experience

Ibu Neng is a 39-year-old high school graduate. Her cooperative’s board entrusted her to operate the BRILink banking agent service in Tangerang’s Kemiri subdistrict. Her journey began with doubts about her ability to run an electronic data capture (EDC) machine and other digital devices. Now, she conducts more than 100 transactions each month. However, she struggles to predict cash flows and manage her liquidity. Her inability to ride a motorcycle also restricts her mobility when she needs to visit bank branches to rebalance her float.

Unlike Ibu Neng, Teh Niar is a 27-year-old tech-savvy woman who graduated from a vocational high school in Karawang district. She is confident in her role as a BRILink agent and often uses YouTube tutorials to learn how to handle various new transactions. Despite competition from a long-established agent in the locality who serves more walk-in customers, she still has a niche market. Niar uses her social networks and cooperative affiliation to serve a distinct set of customers beyond cooperative members. However, she has limited working capital and cannot accept higher-value transactions, which compels her to reject some high-potential customers.

Such stories highlight factors that shape female agents’ realities. These factors include education, social norms, awareness, and the ability and confidence to run an agent outlet. The question is: Will these factors prevent these two female agents from succeeding in their business?

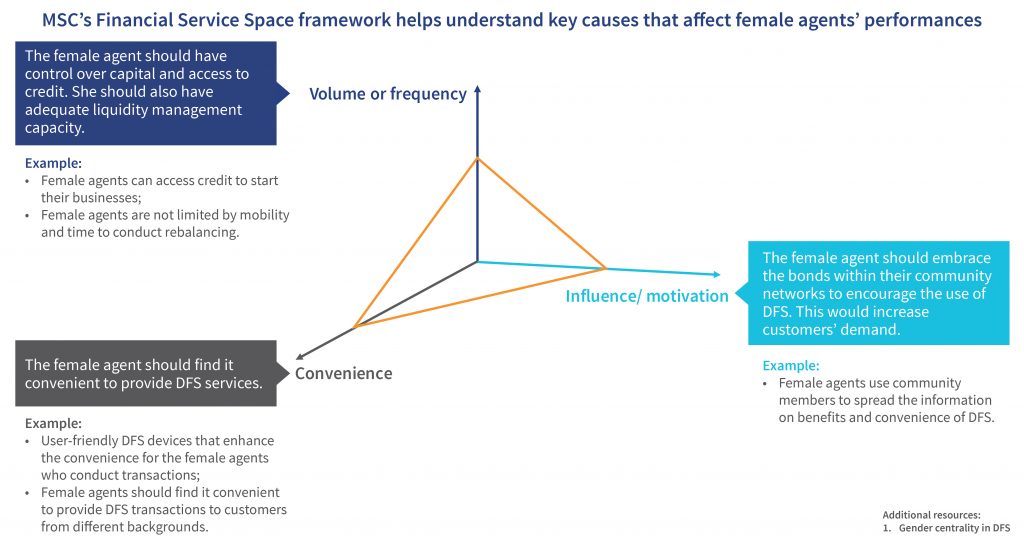

Gender centrality using MSC’s Financial Service Space (FSS) framework

The Financial Service Space (FSS) framework analyzes the environment in which an individual can conduct independent financial transactions. It considers factors, such as transaction volume or frequency, convenience, and influence or motivation. We used this framework to determine how these three aspects affect female agents’ performance.

Toward a path to profitability: How agents can overcome capital shortage and improve their liquidity management capabilities

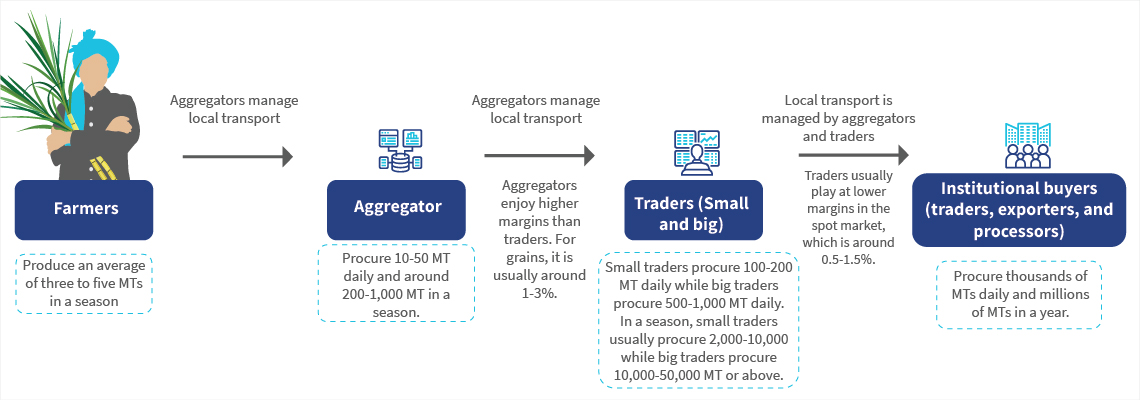

The path to profitability is difficult for female cooperative agents, particularly since they have limited control over capital and liquidity management. They are expected to kickstart their ventures with modest initial capital. The capital usually starts small and increases gradually based on the cooperative’s financial stability. Their challenges are compounded by a lack of familiarity with the projection and management of the agent business’s variable cash flows and mobility-related difficulties in rebalancing.

- Profitable digital financial service (DFS) transactions require higher working capital.

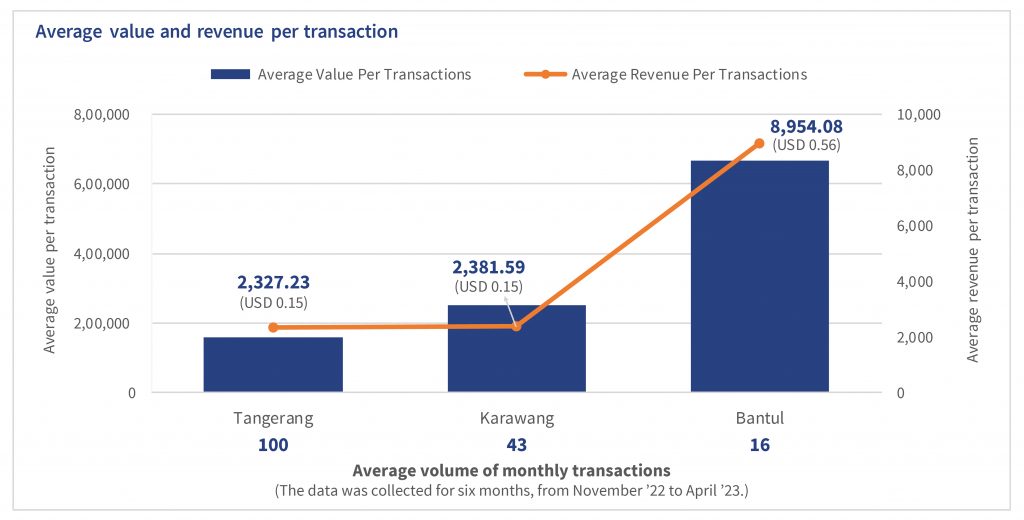

A comparison of the performance of three agents in Tangerang, Karawang, and Bantul reveals that Tangerang leads in transaction volumes, whereas Bantul excels in profitability per transaction. Conversely, despite lower monthly transaction values, Bantul stands out in profitability thanks to higher commissions per transaction. Bantul serves more inter-bank money transfers and cash withdrawals, which earn agents a higher gross commission, (IDR 15,000-20,000 or ~USD 1-1.5 per transaction) before a 50% deduction for bank fees.

Agents can build a sustainable business if encouraged to achieve higher transaction volumes and conduct more profitable transactions. BRI’s recent policy change aligns with this principle as it has shifted from “number-of-transaction-based” to “commission-based” targets. However, this presents an ongoing challenge because these agents have limited capital, which requires them to rebalance more frequently—and thus travel to bank branches. This leads to additional operational expenses and opportunity costs for agents as they strive to meet customers’ demands.

- Variable demand: A liquidity puzzle

Balancing cash and e-float is also a challenge because of unpredictable demand. Moreover, female agents struggle to understand transaction patterns and financial flows, which means they struggle to predict liquidity needs and are forced to undertake irregular rebalancing trips.

A better solution could address the liquidity challenges and improve sustainability for new agents. Besides the provision of rigorous training on liquidity management, an automated system that monitors and forecasts future demand would simplify rebalancing. Indonesian financial service providers may consider such a solution. Nevertheless, the country’s agents crucially need an accessible system that addresses the diverse barriers they encounter.

Convenience for both customers and agents

The integration of women’s cooperatives with agent banking services brings DFS closer to the community. Unlike the conventional agent setting, customers, that is, cooperative members, can access DFS anytime and anywhere by contacting these female agents via phone or WhatsApp. The female agents can collect cash and payments later on through group meetings or visits to neighbors. This fosters familiarity with DFS for rural women who have long relied on cash.

However, agents do not experience the same level of convenience as customers. Female agents often struggle as they adapt to operational, technological, and financial challenges when they start the agent business. While they encounter difficulties in DFS transactions, agents do not rely solely on bank field officers. Instead, agents prefer YouTube videos and WhatsApp BRILInk agent groups as their primary sources for quick solutions to technical challenges. They typically approach bank field officers for more complex technological issues related to the device. Despite occasional struggles, these experiences have bolstered their confidence as they handle a broader spectrum of financial transactions.

Community networks can influence people and spread the word far and wide.

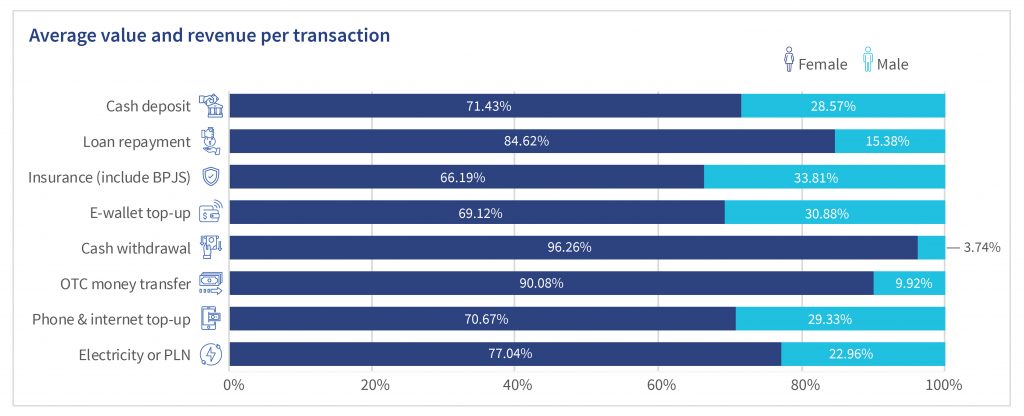

Agents offer incentives to cooperative members who refer DFS to new customers to boost transaction demand and sustain the business. These cooperative members have become enthusiastic advocates for DFS. They actively promote the variety and advantages of DFS and strongly emphasize the convenience of using agent services. Consequently, they have grown into influential marketing agents whose advocacy reaches their families, friends, neighbors, and even those not part of the cooperative. These female cooperative agents play a pivotal role as they enhance financial literacy and foster digital confidence within their communities through established networks and trust.

The criteria for success among female agents’ should extend beyond revenue metrics. While they struggle to meet specific revenue targets, these agents possess a unique ability to influence customers to explore new products and services, which fosters customer loyalty. Research reveals that female customers exhibit distinctive decision-making behaviors when they consider a new product or service. They value peers’ opinions on financial products, which emphasizes the role community networks play to shape their choices.

The development of a gender-intentional financial ecosystem needs collective effort.

In conclusion, if stakeholders overlook women’s empowerment in financial inclusion, it will lead to a significant lost opportunity for both service providers and society. Only if we recognize and address the diverse challenges women encounter in the agent business can we pave the way for a more equitable and economically prosperous future.