Jane is a single mother who works as a casual laborer and receives a weekly wage of KES 4,000 (USD 27). She dreams of a better home for her family. She has tried to secure a housing finance loan from different financial institutions, but her efforts have been in vain. Her unstable income, lack of bank account, lack of a title deed, and absence from any formal group have created insurmountable hurdles to obtain housing finance. Jane represents the 60% of the Kenyan urban population compelled to live in informal settlements. Her story is one of many that highlight Kenya’s pressing issue of affordable housing.

Jane’s story reflects the challenges faced by many low- and moderate-income (LMI) Kenyans who cannot access housing finance. This underscores the national housing crisis and how affordable housing remains a distant dream for the majority. Stories of countless people like Jane highlight the need for systemic change in the housing finance sector.

Access to affordable housing could transform Jane’s and many others’ lives. Homeownership is more than a dream for LMI individuals—it represents economic empowerment, stability, and improved living conditions. For many, it means breaking free from poverty and offers far-reaching benefits, such as access to better education and healthcare and a secure future for their families. It is the cornerstone of a better life and a brighter future.

Affordable housing situation in Kenya

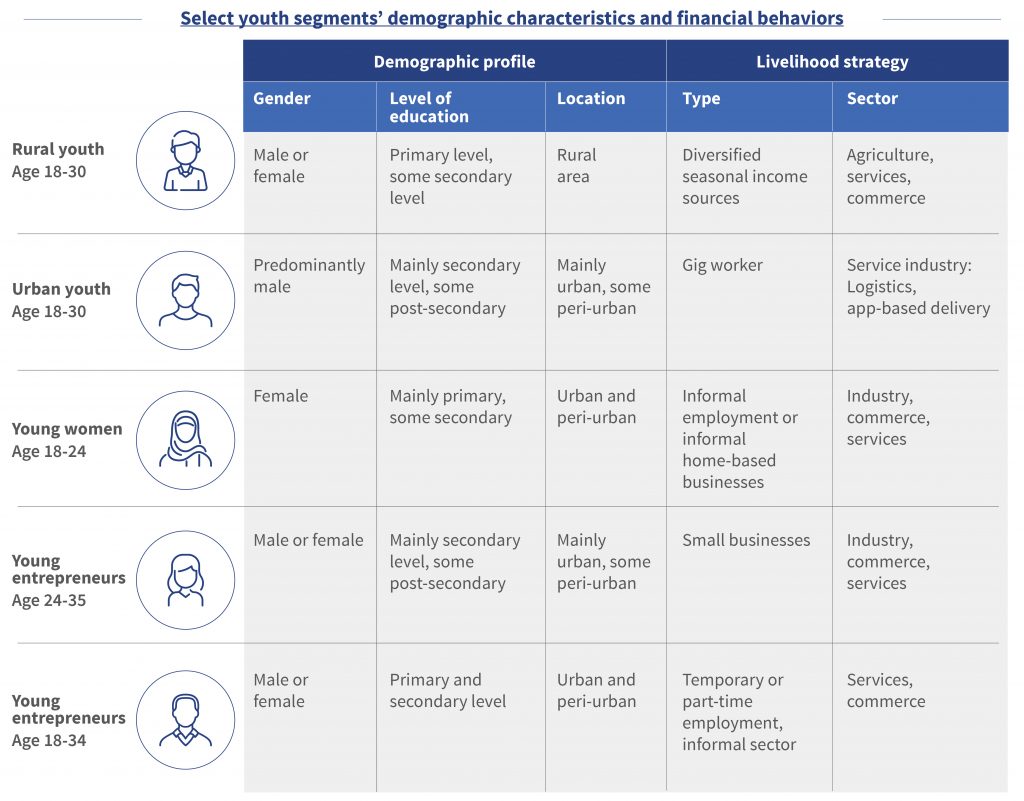

The LMI segment comprises a significant portion of the country’s population and desperately needs housing solutions. Kenya has been grappling with a housing deficit, with only 50,000 units supplied against an annual demand for 250,000 units. The demand for housing is particularly high in urban and peri-urban areas, where most low-and middle-income earners live. The rapid urbanization rate (3.7%) and the increasing number of people in the workforce are expected to increase the demand for housing finance within this segment.

In Kenya, a mere 11% of the population can afford a mortgage. Informal settlements are widespread in the nation. This often forces LMI individuals into substandard housing conditions. These settlements lack proper sanitation, access to clean water, and security. This makes life challenging for those who live there. Government-led programs and financial institutions have been working to make homeownership more accessible to the LMI segment.

Barriers to affordable housing finance

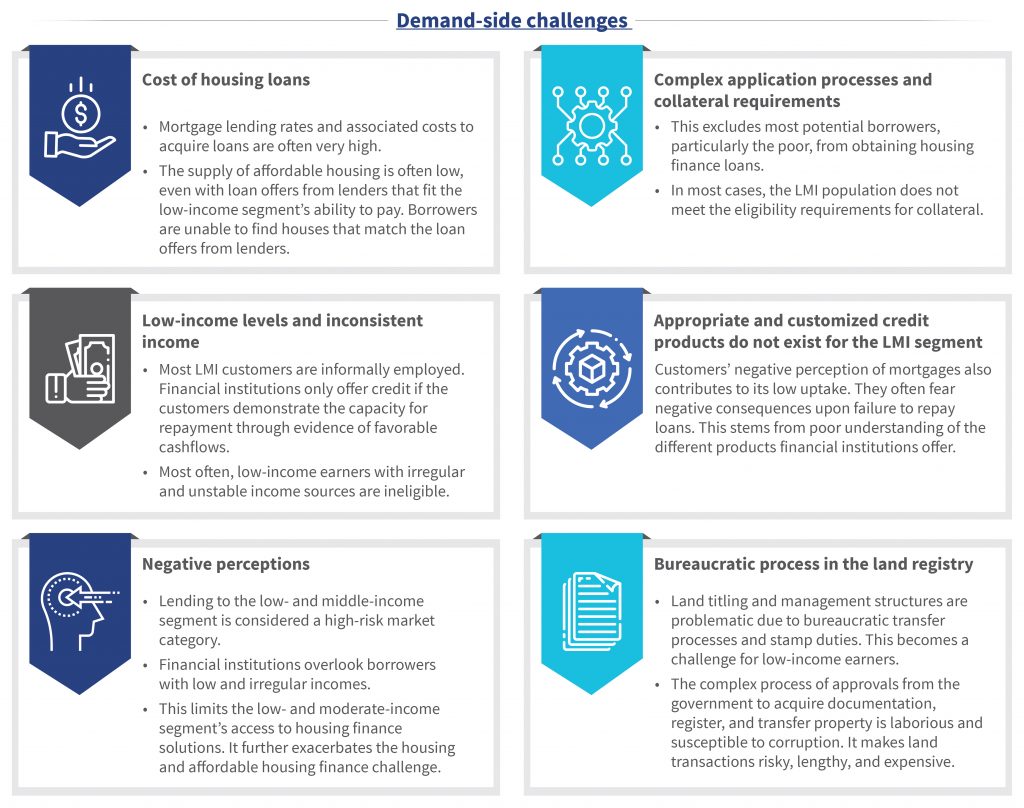

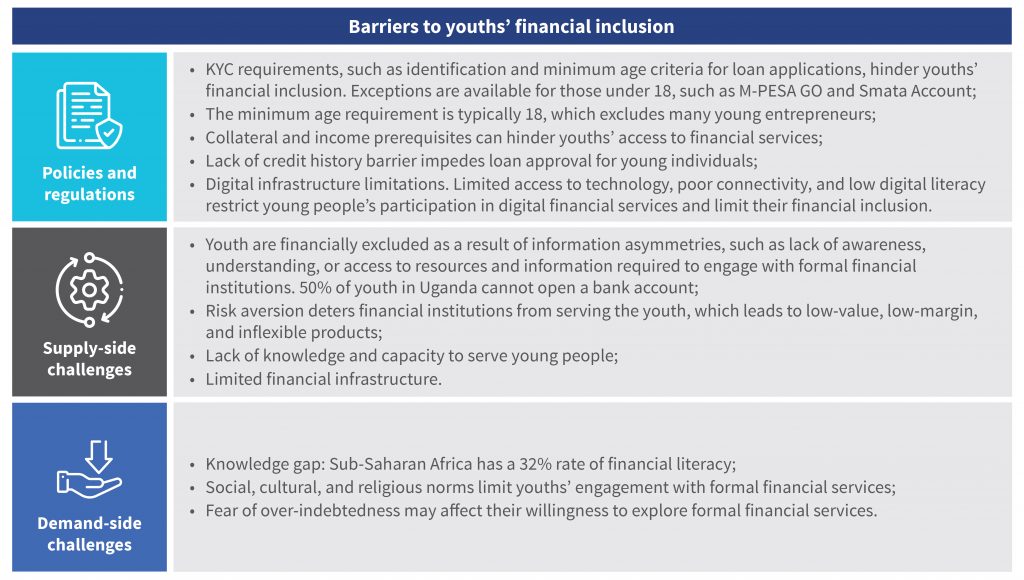

LMI households, such as Jane’s, are often confused about whether they should save for a home or meet their immediate needs. Most Kenyans spend almost 15% of their income on housing. The pursuit of dignified shelter in the absence of affordable housing finance risks the continuation of the poverty cycle. These households face systemic barriers in their access to affordable housing finance besides the effects of low- and unstable income. High interest rates, lack of collateral, and complex loan application and approval processes are just a few systemic challenges that LMI people face.

MSC helped Habitat for Humanity Kenya conduct a study to identify barriers to access and use of housing finance in Kenya. High interest rates and clearing costs were respondents’ most frequently cited challenges (50%). High construction costs and the rising cost of building materials were other significant challenges. Only 2% of newly built houses target LMI families, which drives up the mortgage costs beyond the reach of 89% of Kenyans. The prohibitively high costs to build or renovate a home and high financing costs keep current financial solutions unaffordable for most. The box below shows the barriers LMI people face.

The study underscores the importance of designing housing finance products that specifically cater to the LMI segment’s needs and financial capabilities.

Designing the right housing finance products

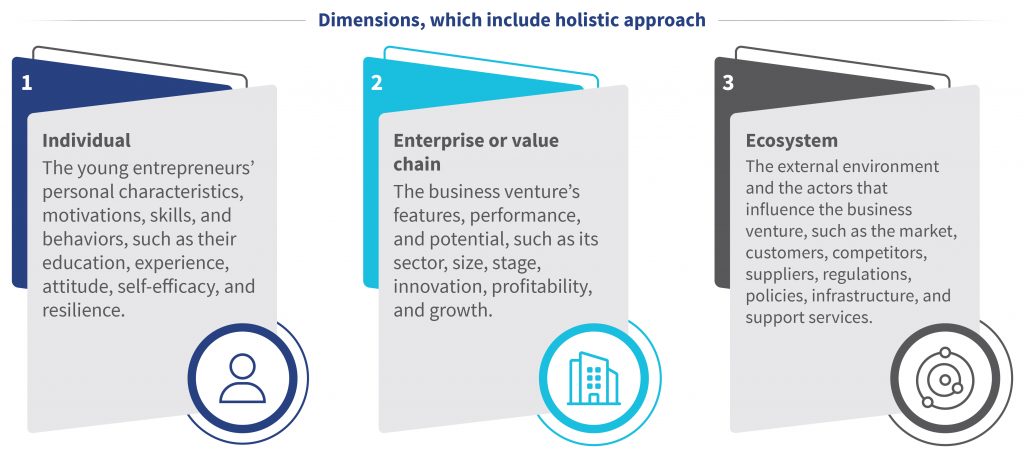

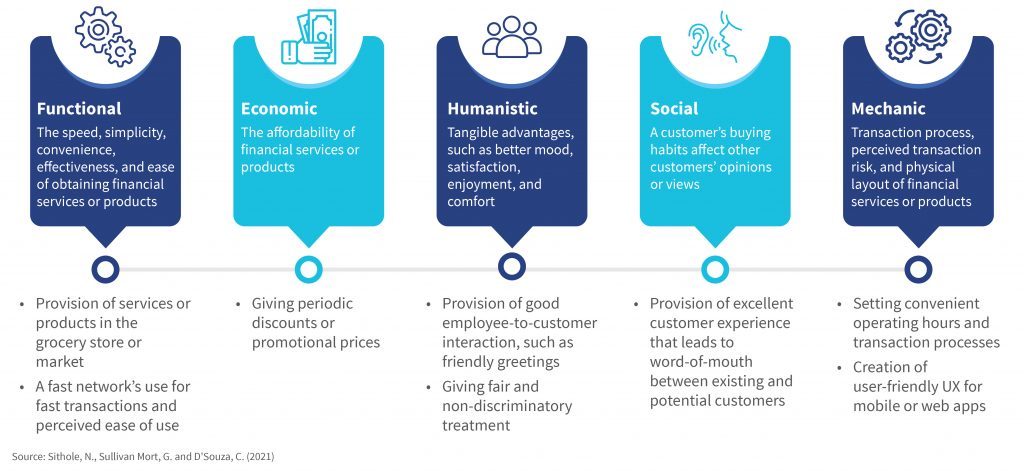

Product features play an overwhelming role in consumers’ borrowing decisions. MSC’s survey results indicate that convenience is a significant factor as individuals opt for solutions that are easily accessible and user-friendly. Affordability is another key driver of consumer preference, as borrowers prioritize solutions that offer low repayment amounts tailored to their financial capacity. Moreover, financial service providers who target and prioritize specific geographies, such as rural areas, significantly improve the level of access to housing finance LMI earners in those regions enjoy.

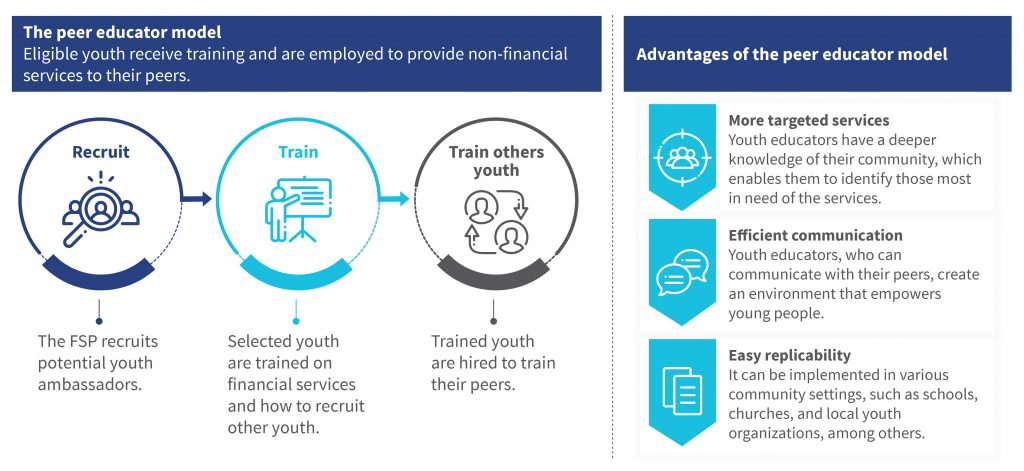

Delivery channels significantly impact the access and usage of housing finance. Delivery channels need to be hybridized to ensure greater reach and accessibility to housing finance as implemented in other sectors. This process combines traditional physical branches with digital platforms. Similarly, a well-designed and targeted marketing strategy significantly impacts the awareness, perception, and usage of housing finance products. For example, Habitat for Humanity’s Terwilliger Center for Innovation in shelter has worked with financial service providers to help them design their branding and marketing strategies. This approach positions housing microfinance products as opportunities for LMI households to achieve their dream home in stages, through a series of successive loans tailored to their affordability.

Financial service providers can benefit immensely if they understand the LMI population’s unique needs and constraints. Although incremental construction for the LMI segment is mostly tied to housing microfinance, such as home improvements, the model can potentially extend to housing construction. Some SACCOs and MFIs offer micro-mortgages that adopt the incremental lending model. This approach tailors housing development to the borrower’s financial capabilities and generates a demand for previously non-existent loans.

These findings should drive the financial service providers to develop solutions that are easy to use, convenient, affordable, and tailored to their target customers’ needs. By doing so, they can increase the uptake and usage of their housing finance products and services and better serve their customers’ housing needs.

The untapped potential for home ownership within the LMI segment

Serving the LMI segment is a public policy imperative and offers a sound business case. The demand for affordable housing is undeniable. If we unlock the segment’s potential, it would bring several economic opportunities waiting to be tapped.

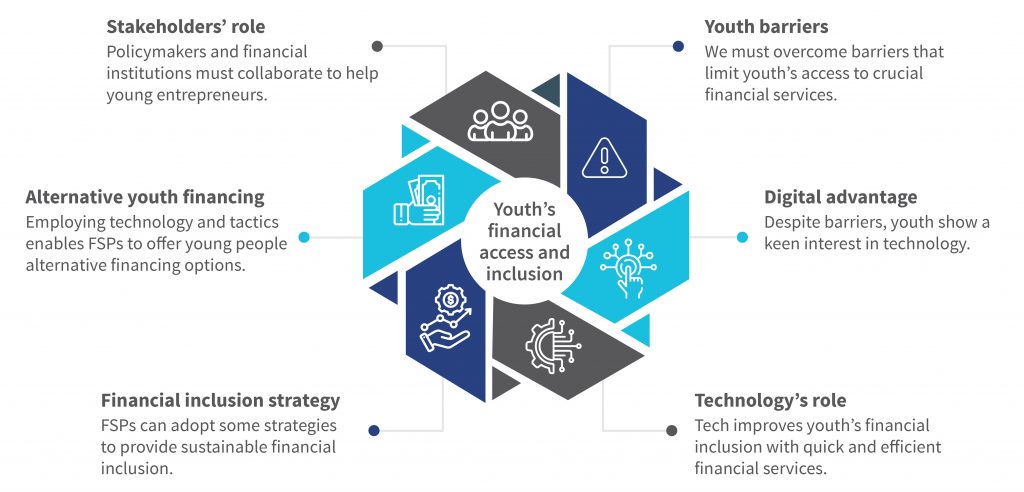

The untapped potential primarily stems from financial barriers that have traditionally hindered the LMI segment’s homeownership. Financial inclusion plays a pivotal role to make homeownership a reality for the LMI segment. Tailored financial products can provide necessary support, such as affordable mortgage options and down payment assistance programs. The Kenya Mortgage Refinance Company (KMRC) has enabled lending through savings and credit cooperative societies. It, thus, made homeownership more accessible for LMI households in Kenya.

Another common barrier to homeownership in the LMI segment is the perceived challenge to obtain credit. Mechanisms for fair credit evaluation and recognition of alternative forms of creditworthiness can empower individuals with limited credit histories. This inclusivity is not just a social imperative but also a key driver for economic growth within communities.

Our next blog explores the opportunities for donor investment in housing finance to promote financial inclusion.