Are we over-selling start-ups as a career option?

by Graham Wright, Anil Gupta and Abhinav Guptha

Feb 17, 2022

6 min

Every startup success story shows up alongside 10 failures; still, entrepreneurship is an attractive career proposition for our youth. In more than 90% of cases, the founders would fail to repay these loans, leaving meaningful relationships with their trusted ones fractured and damaged. Is this a price worth paying? This blog discusses an unfashionable perspective on starting up and shares our experience accelerating startups in Asia while orienting them toward success.

A little personal history

In 1983, as I was training to be a chartered accountant, I worked with Peter Risdon and Lord Trevor-Roper on a start-up to challenge the optician’s monopoly on reading glasses in the UK. In those days, basic reading glasses cost more than £40 a pair – even though they could be imported for less than £1. Opticians asserted that people needed an eye test to identify the appropriate reading glasses. This was clearly wrong, and as a result of our “For Eyes” start-up, the Optician’s Act of 1958 was amended. As a result, in the UK, as in the rest of the world, anyone can buy reading glasses for £1.

We were naïve entrepreneurs and quickly ran into the classic start-up’s liquidity problem as we had to pay suppliers before we had the cash from the roaring sales at our modest shop in Clerkenwell in London. After much heart-searching, I pitched our business to my Father and secured a loan of £10,000 – no small sum. We struggled on, refused a take-over bid (I said we were naïve), and eventually For Eyes collapsed, and I had to return to my Father empty-handed, only able to offer apologies.

Harsh realities facing start-ups across the globe

This story is common amongst start-ups across the globe – friends and family are roped in to finance aspirations and dreams of young wannabe entrepreneurs with big plans and small bank balances. In the last decade, we have lionized these entrepreneurs. We have placed them on pedestals and sold the idea of building “unicorn” tech start-up companies as part of the digital revolution. Some are realizing those dreams, and many are developing valuable products and services to make our lives more convenient.

But the success stories are not the norm … The Global Entrepreneurship Monitor (GEM)’s research shows that there are “about 300 million people who are trying to start 150 million businesses worldwide … there are about 50 million new businesses each year”. So, globally, there are roughly 137,000 start-ups daily … but around 120,000 businesses close each and every day.

For every single success story, there are around ten failures. Investopedia notes that “in 2019, the failure rate of start-ups was around 90%.” It highlights that “reasons for failure include money running out, being in the wrong market, a lack of research, bad partnerships, ineffective marketing, not being an expert in the industry, and particularly for, tech start-ups, wrong timing.”

A recent NetshopISP article noted that each year, “1.35 million [start-up] businesses are tech-related.”

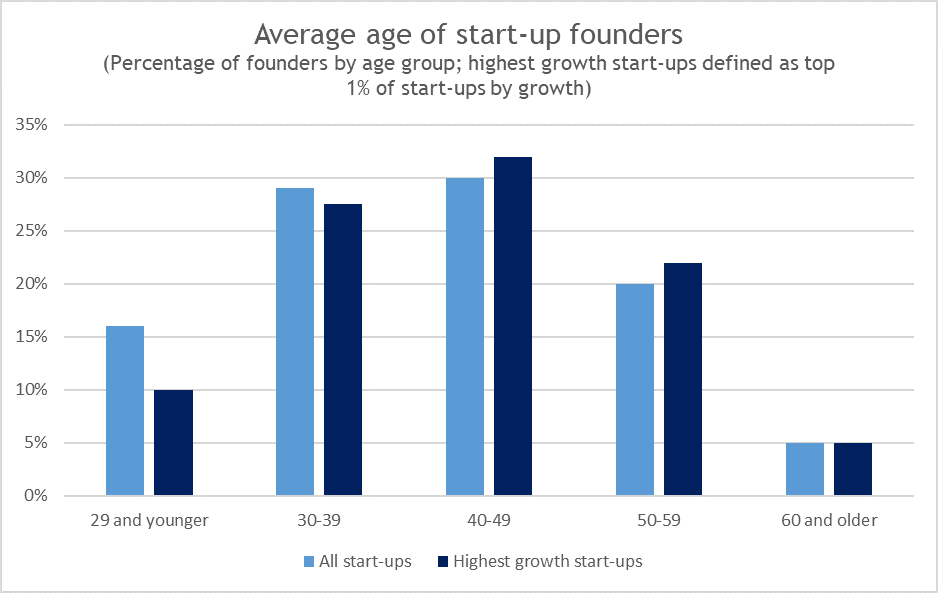

The popular image of tech start-ups is of geeky students operating out of their dorms – but these are less common and indeed less successful than their more mature, experienced counterparts. US Census Bureau and MIT research showed that tech entrepreneurs aged 60 years are nearly four times more likely to found a successful start-up compared to entrepreneurs who are in their mid-20s. The average age of a successful start-up founder is 45.

StartupsUK highlights a similar pattern, noting that, “Most small business employer owners and co-owners fall into the 35 to 44 (25%), 45 to 54 (31%) and 55 to 64 (26%) age categories. The proportion in older cohorts is much smaller; just 7% over 65.”

Source: Age and high growth entrepreneurship – Pierre Azoulay et al 2018

MSC’s experience with start-ups in Asia

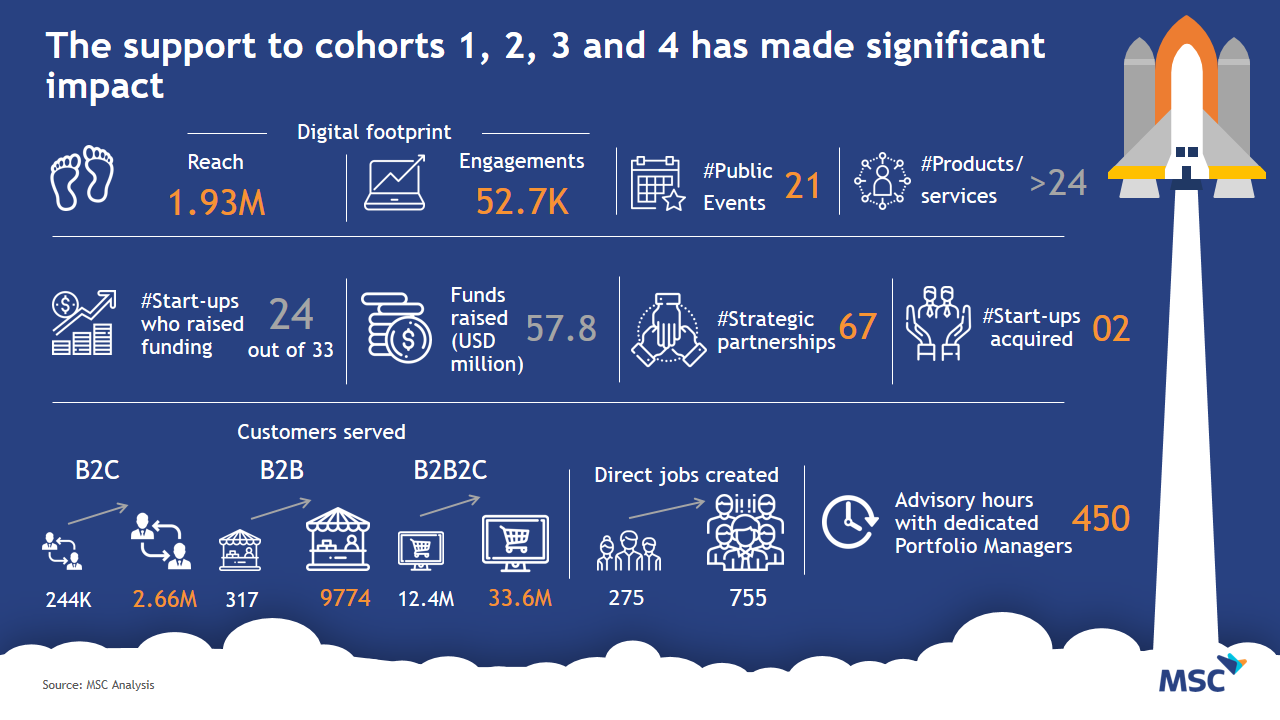

MSC’s acceleration labs and related work in India, Bangladesh, and Vietnam nurture start-ups in their growth stage to deliver appropriate solutions to serve low- and moderate-income (LMI) people. Due to the extensive support that these start-ups receive from the lab, their probability of success is high. Though not representative of the whole market, these start-ups highlight interesting perspectives and data on the start-up universe.

1. Selection funnel – the blessed 4%

- There are too many ideas, but very few of them were selected for support through the labs. MSC-supported acceleration programs have already received over 1,100 applications. However, only 44 (4%) of those start-ups have received or are receiving support.

2. Age of entrepreneurs

- In India, the Business Standard reports, “The workforce in the age group of 45-54 years (37 percent) are hesitant to start their own business as compared to the workforce in the age group of 25-34 years (72 percent) and 35-44 years (61 percent).” So it is unsurprisingly perhaps that the average age of the founders in our cohorts in India is 34.5 years – experience makes an important difference. However, we have also seen a few young co-founders setting up start-ups. However, most of the start-ups have co-founders with complementary capabilities to mitigate the risk of failures and add years to their cumulative experience as they steer the start-up.

3. How many have borrowed from family and friends? How many still owe family and friends?

- Almost all the start-ups in our cohorts have taken money from friends and family – unsurprising considering the relatively early stage of their ventures. It is difficult (and sensitive) to ascertain if they still owe money to their friends and families. However, one-third of the cohort start-ups have already raised money from institutional investors – we can safely assume that this could help them return, at least part, some of their borrowings from friends and family.

4. Type of support-services provided

- Start-up founders and their teams build digital products. However, it requires an extensive understanding of the LMI segment to ensure user value. Our labs support founders to understand their customer segment better and design products with a better market fit. This ensures quicker adoption and higher usage of the products and increases the success rate of the start-up. For example, Lakshya is a digital savings platform that provides access to formal savings and insurance to India’s LMI segments. The lab helped them with customer segmentation and enabled Lakshya to design financial products that catalyze the economic well-being of their customers.

- The rise of digital engagement has enabled founders to launch products with near real-time decision-making capability on processes like customer onboarding, underwriting, payments, and so on. In this context, start-ups must have a strategy to deal with poor quality of data architecture, management, and analytics. Our labs are mentoring start-ups to formulate robust strategies to develop and implement efficient data-centric processes. Finarkein Analytics focuses on simplifying the information value chain through its unique and innovative data analytics solution. Our lab supported them to understand the account aggregator data ecosystem in India, streamline their current processes, and formulate a robust pricing strategy for their services.

- Go-to-market is key to scaling up product adoption and usage. Many early-stage start-ups suffer despite achieving product-market fit as they struggle to onboard the right customers to use the product. Insufficient product traction directly impacts the investment cycles and becomes a potential risk for failure. Our labs help start-ups identify channels to reach LMI customers efficiently and collect feedback from these users. This enables founders to refine the product and achieve a larger customer base. Fundfina is a digital lending platform providing access to formal credit to micro and small enterprises (MSEs) in India. The lab’s support helped them understand the segment-specific behavior and craft a marketing strategy to reach 10 million small enterprises in the next five years.

- Undoubtedly collaboration is key to startup success. Businesses with innovative products and limited resources must find partners to scale efficiently. Through our labs, startups get a chance to interact and work with partners/enablers like non-banking financial companies (NBFCs), farmer producer organizations (FPOs), corporates, policymakers, banks, and so on in the ecosystem. This results in quick scaling, increased efficiencies, and better unit economics, which directly contributes to the founder’s success. Whrrl, an agritech startup from our cohort uses a blockchain-based disruptive financing model to fund farmers. Our lab has enabled them to partner with various FPOs, warehouses, and agri-institutions to engage farmers.

These challenges were amplified by the COVID-19 pandemic.

These trials and travails reflect the challenges that even the most successful start-ups face … and, despite being in the carefully selected top 4% of start-ups, and despite the extensive support from the labs, many struggle to survive.

The concern

Despite this, start-ups are promoted as a credible career option for young people more than ever before. One colleague received a mail from his son’s high school promoting the idea of start-ups as a career. And the papers are full of success stories, but rarely mention the many more failures. Society seems to favor glorified stories on young adults making it big, without going into too many details of the struggles involved. We risk encouraging millions of, often naïve, aspirant entrepreneurs to start a business when they are least equipped – financially and in terms of experience – to do so. We may well be doing them a disservice by hyping tech start-ups and selling the unicorn dream. Furthermore, as I can attest from personal experience, the need for financial support drives young, poorly resourced entrepreneurs to borrow from their families and friends. In >90% of cases, these loans will not be repaid from the start-up, leaving important relationships fractured and damaged. Is this a price worth paying?

by

by  Feb 17, 2022

Feb 17, 2022 6 min

6 min

Leave comments