Paint by numbers: Profiles of bank agents in India

by MSC

May 16, 2013

3 min

MicroSave carefully looks at the agents’ books to understand the underlying problems facing agency banking in India and how best to address them.

India’s financial inclusion efforts remain in a difficult transition period. And agents, or business correspondents, as they are known here, are not the all-purpose, “last link” solution everyone had imagined between banks and low-income, remote or migrant customers.

Despite the Reserve Bank of India’s (RBI’s) commendable efforts to move financial inclusion aggressively forward (this year’s target is ~200,00 agents, a fourfold increase from 2011), almost no one immediately involved with these efforts is happy right now. (Please also see MicroSave’s blog on RBI’s new, more relaxed rules regarding businesses and banking licenses.)

It has been tempting in some circles to imagine that agents and their managers are simply not trying hard enough. Both are too easily discouraged and too quick to complain when easy profits are not forthcoming.

One reason for these assumptions is that much of the evidence thus far has been either anecdotal and qualitative, or one-sided (usually from the banks’ or microfinance institutions’ perspective).

MicroSave decided that a careful look at the agents’ books might help all parties better understand the specifics of the underlying problems and how best to address them. (Please see MicroSave’s Rapid Agent Assessment for more details.)

The specifics do indeed help explain the agents’ discontent.

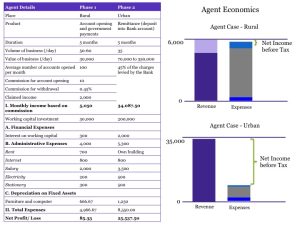

Urban business correspondents who offer migrant-worker remittance services, the most lucrative source of revenue, in shops that attract constant traffic can clear almost Rs.10,000(~US$185) in monthly profits. But these instances are rare (only 2-3%).

The more normal situation for these agents is close to break-even with little hope of achieving their net-income expectations of Rs.20,000-30,000 per month. Rural agents fare far worse with less access to remittance income and markedly lower commissions (sometimes by as much as a factor of 10).

Agents’ books also reflect:

- Erratic commissions and late payments;

- Technology delays that cost them money and customer trust;

- Little support for marketing and advertising;

- Even less contact with the banks they are representing.

The agents’ managers aren’t making money either. Their woes include:

- Low/no cooperation with the banks;

- Agent inactivity, which MicroSave estimates to be as high as 73%, and churn (many new agents quit after nine months or sooner);

- Unreliable bank servers and connectivity, particularly in rural areas;

- Liquidity management, insurance, security risks for both their cash-in and cash-out agents;

- Late bank payment of agent commissions.

Nevertheless, the almost daily server downtime, plus high agent turnover in many areas, mean rural customers in particular have two unappealing choices: a less than trustworthy agent and transaction, versus the travel time and long queues involved in making deposits and withdrawals at bank branches a far remove from their village.

A number of solutions are under discussion including better agent training, improved incentives, and shared insurance that helps protect agents’ liquidity risks at lower costs. The real dilemma, of course, is human fallibility. India’s finance ministry has committed to doubling the number of ATMs to 200,000 in every corner of the country by the end of next year, despite the high costs of installation and maintenance, at least in part due to the insoluble problems posed by agent networks.

However, for the foreseeable future, two lakhs worth of ATMs can hardly hope to serve the needs of 1.2 billion citizens, of whom ~41% remain unbanked, according to the Bank of India. Agents, like the poor, will probably always be with us. Better solutions for these last links are important for financial inclusion to move forward and succeed.

by

by  May 16, 2013

May 16, 2013 3 min

3 min

Leave comments