Overcoming the roadblocks in India’s rural road connectivity program

by Diganta Nayak, Subhash Singh, Vikram Sharma and Pranav Mehta

Apr 15, 2024

6 min

The Pradhan Mantri Gram Sadak Yojana (PMGSY) was launched in 2000 to connect rural areas with all-weather roads for better access to essential services. However, the program faced operational challenges, such as poor visibility of funds, manual data entry, and lack of transparency in contract compliance. MSC recommended the implementation of the smart payments solution (SPS) to tackle these challenges. Read the blog to learn how the SPS’ success can eventually act as a blueprint for nationwide infrastructure projects to bridge the divide between urban and rural infrastructure in India.

The urban skew in infrastructure development

Vast income disparities persist between urban and rural India. Nearly 25.7% of the rural population remained trapped below the poverty line, compared to 13.7% in urban areas.

The Indian government has been acutely aware of this gap and has thus made focused interventions to improve rural infrastructure. The Pradhan Mantri Gram Sadak Yojana (PMGSY) is one such program that the government launched in 2000. It has become one of the Indian government’s most celebrated programs. Under PMGSY, the government seeks to connect unconnected rural areas through all-weather roads to ensure access to economic and social facilities in nearby urban centers. This includes access to markets, healthcare, and education.

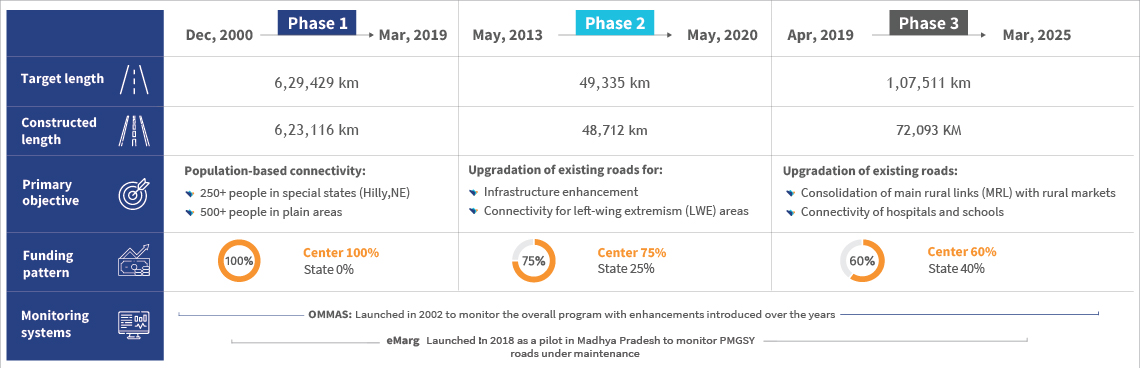

Since its launch, the program has overseen the completion of nearly 760,000 km of road length as of April 2024. The project is in its third implementation phase and intends to add another 100,000 km of road by the end of March 2025.

Figure 1: Two decades of connecting rural India

Source: OMMAS dashboard

An overview of the PMGSY

The National Rural Infrastructure Development Agency (NRIDA), under the Ministry of Rural Development (MoRD), Government of India, executes and monitors the PMGSY program. PMGSY follows a three-tier structure. The NRIDA, at the national level, coordinates with multiple State Rural Road Development Agencies (SRRDA) that oversee the execution of works via the District Project Implementation Unit (DPIU) at the last mile.

The program is divided into two phases: construction and maintenance. The construction phase is usually completed within a year, after which the road enters the maintenance phase for the next 10 years. Both phases are executed on a separate set of operating principles and are planned and monitored through different IT systems to ensure smooth and efficient operations. The construction phase is monitored via the Online Management, Monitoring and Accounting System (OMMAS), whereas the maintenance phase is managed via electronic Maintenance of Rural Roads under PMGSY (e-MARG).

Multiple operational and systematic challenges continue to impede the program

Right from its inception, PMGSY had well-defined operational and financial guidelines for all stakeholders. It has continuously adapted to keep pace with changing times and has added new policies and technical interventions. However, MSC’s diagnostic study of the program’s construction phase revealed significant scope to improve efficacy and efficiency.

MSC conducted this study in Haryana, Madhya Pradesh, and Punjab to identify key issues. We used a framework of digital public finance management (PFM) principles, such as a single source of truth or data, digitization of inputs at source, and de-monopolization of access to services. We identified the following issues through the study:

- Low visibility of fund availability for stakeholders: The public finance management system (PFMS) only captures the amount released from the center to the state. However, once the fund leaves the Single Nodal Account (SNA) at the state level, the MoRD has limited visibility on the funds allocated to and used by DPIUs. Fund status is only accessible once district units voluntarily upload spending summaries, subject to their discretion. This lack of fund visibility and bill traceability in the OMMAS often results in the underutilization of funds or impedes their timely release.

- Manual feeding of work data in the OMMAS: All payment conditions are recorded manually with a paper trail. For example, entries from the measurement book (logbook maintained by DPIUs to monitor and record construction activities), and the measurement bill book (logbook maintained by DPIUs to calculate and record payments for construction completed), are uploaded with only values entered, into the OMMAS. Compliance-related or other supporting documents such as quality test reports, labor compliance certificates, contractor bills etc. are not uploaded on OMMAS. Hence, the team that processes payments has to wait for and rely on the physical file that contains paper documents. This increases the administrative burden, leads to duplication of effort, and delays payment processing.

- Entitlements are calculated manually and uploaded on the OMMAS: The DPIU staff calculates all entitlements and makes adjustments manually based on contract service level agreements (SLAs), as well as other adjustments, such as penalties and advances, among others. The basis for the final payment calculations is not traceable in the OMMAS. This leaves scope for staff discretion when they finalize the payment amount and prepare the payment voucher in the OMMAS.

- Low transparency or traceability in compliances linked to a contract: After contracts are awarded, the OMMAS only receives the tender information and details around the award of contracts through the digital procurement system called the Government eProcurement system of NIC (GePNIC). These details include bid type, date, number of bids, and bidder’s name and contract value. However, contract clauses are not exported to the OMMAS, and staff have to maintain physical records of the contract, which leads to limited transparency and traceability.

Integration of the smart payments solution

Based on the diagnostic study, the MSC team recommended the smart payments solution (SPS) to facilitate more efficient fund management and rule-based payment processing. The major components designed to enable SPS implementation were as follows:

- Single project registry (SPR): The SPR will be a reference data repository for all PMGSY projects based on the principle of a single source of truth. The SPR will hold all project-related data and information at one point and enable access to real-time information to and from other applications. This information includes vendor data, contract milestones, and payment conditions, among others.

- E-measurement book (eMB): The proposed eMB will be a part of the modular architecture and work in sync with the OMMAS as a workflow management system. The eMB will enable data entry of a contractor’s work at the source digitally and allow rules-based processing to fulfill compliances. The data processed in the eMB will trigger the smart payments engine (SPE) to automatically generate the measurement book and measurement bill book, thus eliminating the need to record work data and undertake any payment calculation manually. Additionally, the eMB will integrate with the existing OMMAS system, allowing for seamless data exchange.

- Smart payment engine (SPE): The proposed SPE refers to a module that runs if-then-else algorithms at the backend. It uses available inputs in electronic form and other payment conditions. The SPE will automate invoice processing and voucher creation, and provide the necessary trigger to release funds to vendors.

Lastly, the integration of SPS with the treasury single account (TSA)—currently piloted by NRIDA—will enable the “just in time” functionality. This, in turn, will ensure direct disbursement of funds to the contractor’s bank account instead of cascading through multiple levels.

The three components will function in tandem. The SPR will act as a central hub for all project data to ensure a single source of truth. The eMB and SPE will facilitate compliance through rule-based processing and ensure frictionless payments to beneficiaries. This will pave the way for a more streamlined and automated system that promises increased efficiency and transparency. MoRD had shown full commitment to deploy the SPS.

A blueprint for other infrastructure projects in the country

Once implemented individually or in tandem with the TSA, the SPS will improve program monitoring and efficiency in the short term through real-time updates, fixed locus of accountability, and increased observability. In the long term, these interventions, combined with the TSA, will ensure frictionless expenditure, reduce float at different government levels, and strengthen the government’s fiscal position.

Moreover, we expect the project to emerge as a blueprint for other infrastructure projects across India. We have already implemented the SPS for the Government of Odisha under the MUKTA urban wage employment program. The interim impact evaluation of the program has shown promising results. As these interventions stabilize, they can provide the necessary templates to explore convergence with other programs, such as the Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Act (MGNREGA), the National Skill Development Mission (NSKDM), and the 15th Finance Commission. Such convergence will improve the effectiveness of program delivery and bridge the manifest urban-rural divide in India.

by

by  Apr 15, 2024

Apr 15, 2024 6 min

6 min

Leave comments