Weaving a financial security net for Bangladesh’s garment workers

by Samveet Sahoo, Anik Muntasir Chowdhury and M.K.M. Wahid Uddin Robin

Feb 2, 2022

6 min

The readymade garments (RMG) industry has been a boon to Bangladesh’s economy by earning more than 10% of GDP and contributing to 84% of the country’s export earnings. Though most RMG workers started receiving wages through MFS wallets during the COVID pandemic, many do not have a formal bank account. Consequently, they cannot access a bouquet of financial products, such as credit, savings, insurance, and so on. Financial providers barely translate these needs into products and services that can serve RMG workers. However, they can cater to an untapped segment if they adopt an innovative design approach. Partnership with social enterprises that offer services to RMG workers can play a pivotal role here.

The readymade garments industry is called the “golden goose” of Bangladesh, given its large contribution to the economy. However, the financial health of workers in this industry is far from golden.

Most garment industry workers do not have a bank account. They dream of buying land or livestock, but neither banks nor lenders today provide suitable options to help them attain these goals. Ideally, these workers should use multiple financial products, such as goal-based savings accounts, nano loans, and micro-insurance. In short, they are a readymade market waiting to be tapped by financial services providers who use an innovative approach.

Financial health of garment workers

The readymade garments industry contributes more than 10% of the gross domestic product of Bangladesh and employs around 4 million people, primarily women. Given the importance of this sector, Bangladesh must empower workers in this industry by providing them decent work and better wages and helping them secure their financial future.

At the moment, the financial health of these workers is precarious. Their median monthly income is between USD 70 and USD 300, while their household income is double the amount. Around 60% of the household earnings are spent to cover day-to-day expenditures, according to data from Microfinance Opportunities (MFO), which studies women workers in the garment industry. An additional 28%–33% of these workers’ earnings go toward unusual expenditures, such as unexpected health issues, weddings, or funerals.

In 2020, around 2 million workers opened the “mobile financial service” (MFS) accounts that provide financial services through a mobile phone. To curb the spread of the coronavirus, Bangladesh Bank had made it mandatory for the garment industry to pay employee wages and allowances through these mobile accounts.

Mobile financial services or MFS accounts can be used as digital wallets to receive money and make payments, such as to buy groceries. However, workers in the garment industry cannot use these accounts to their full potential. Although these accounts can be operated on basic or feature phones, some services are best accessed through smartphones. However, only 40% of women workers in the garment industry use smartphones. Among these women workers, many do not own a smartphone or use smartphones borrowed from their partners or family members. Besides, these workers are not trained to use digital wallet accounts and find them complicated to use.

Meanwhile, as the worst of the pandemic has subsided, many employers have gone back to giving wages in cash. This warrants the need for a different, more innovative approach to bring financial services to garment workers.

Different strands of financial services

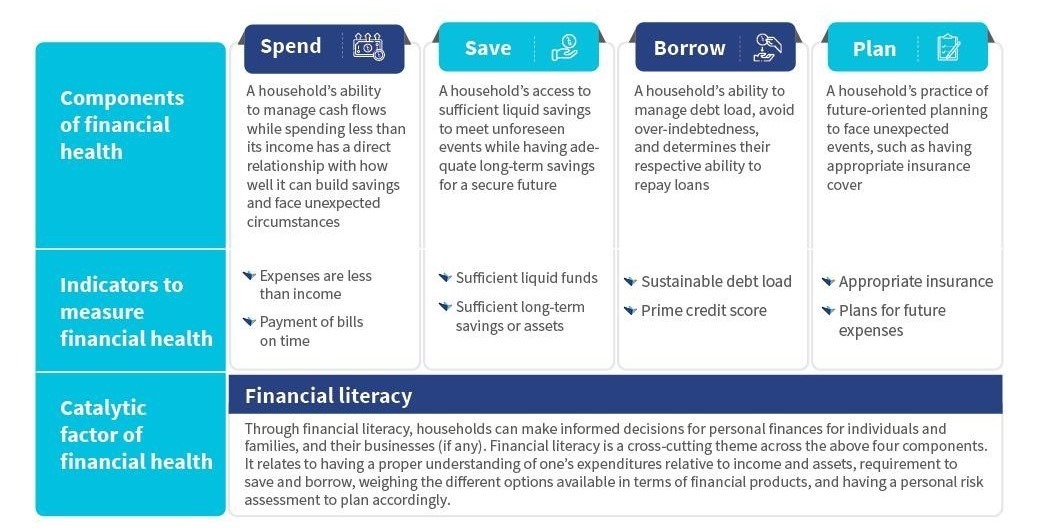

In 2020, MicroSave and Apon Wellbeing, a local partner that runs discount supermarkets within garment factory premises, surveyed garment industry workers to understand their lifestyle and needs. The study found that these workers require a bouquet of financial products and services across the dimensions of saving, spending, borrowing, and planning and protection from exigencies.

Figure: Components of financial health

1. Savings: Many garment workers hope to buy land in their villages, build a house, or buy a sewing machine or livestock, which will generate income after retirement. One approach to help them achieve these dreams would be to offer them goal-based savings products.

In more digitally-savvy markets like India, smartphone applications like EasyPlan or Lakshya encourage users to save money in small amounts, provide a return on savings, and give the flexibility to withdraw money anytime. Micro-savings products based on similar principles can be created for garment workers in Bangladesh. Ideally, these products should also be accessible on basic or feature phones.

2. Credit: Our study of garment workers showed that they are keen to borrow money, often to meet household expenses or emergency expenses such as on healthcare. They typically borrow from their family and friends or take a loan ranging between USD 10 and USD 60 from their managers to be repaid with interest. However, they do not understand how the interest is calculated, making them vulnerable to overcharging.

Meanwhile, banks and financial services providers are wary of lending to this segment, partly because they view them as risky. Financial services providers can start by offering savings products to garment workers and give them short-term loans gradually to overcome this perception of risk associated with lending.

3. Insurance: Few workers in the readymade garments industry have either health or life insurance because they lack knowledge about insurance or find the premiums too costly. However, they are a ripe market for nano-insurance products to safeguard them from sudden health expenditures or disruption to their regular income, similar to what happened briefly during COVID-19.

4. Tailored Financial Education: It is essential to educate workers about managing their financial life. Rather than giving generic information, it should be tied to decisions of immediate relevance and presented at a “teachable moment.” For instance, they can be informed about investment options to multiply their money when they receive their salaries. It is best to steer clear of financial education, essentially product marketing for financial services providers.

Opportunity for financial services providers and FinTechs

Companies need an innovative approach toward product design to create suitable financial products for garment workers. An ideal product should be intuitive, simple, and easy for customers to comprehend and use. The product should include all components of financial literacy and cater to “oral” customers, that is, individuals who cannot deal with written text or numbers and are more comfortable with visuals. MSC has suggested a conceptual wireframe called mobile wallet for oral segments (MoWo) in its earlier work for “oral” people. We believe MoWO is the first step toward the financial inclusion of “oral” people. Providers can use these models or build more local models to train their agents and further educate the garment workers.

An ideal financial product for small-income earners, such as garment workers, would include notifications or a “nudge” component that alerts users to make the next deposit or pay the next loan installment. Such notifications are easy in a fully digital model, say through a mobile phone, but most garment workers do not have a smartphone. So, a more suitable solution for garment workers would be an assisted or “phygital” model—combining digital solutions with a human interface.

A network of agents who have access to technology and smartphones and can educate the garment workers about various financial products, ways to use these products, and potential adverse outcomes can be helpful for the garment workers. Workers would benefit from dedicated banking agents like this, through whom they can get information about their savings or loans.

While Bangladesh has a network of bank correspondents and agents for mobile financial services, these agents are not based inside garment factories, making it costly and cumbersome for garment workers to reach these agents. Workers prefer to interact with someone close to their factories to avoid traveling far.

Social enterprises such as Apon Wellbeing, which serve the community of readymade garment workers, can play a role here. Through its supermarkets, Apon is already connected with garment workers. It allows them to buy products on credit and recovers the money through direct deductions from workers’ salaries.

Apon can collect and analyze data about the buying and credit patterns of these workers, which in turn can be used by banks or financial technology firms to provide savings, credit, and insurance products for garment workers. Once providers start lending to these workers and get comfortable about their creditworthiness, they can offer a host of other financial solutions.

The initiatives discussed in this blog, if implemented, can help give workers in the readymade garment industry better control of their household finances and make their future golden too.

by

by  Feb 2, 2022

Feb 2, 2022 6 min

6 min

Leave comments