Did MGNREGA mitigate the loss in income and unemployment caused by the COVID-19 pandemic?

by Kritika Shukla, Mohak Srivastava and Vedika Tibrewala

May 28, 2021

7 min

The case study discusses the sudden surge in demand for work under the Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Act (MGNREGA) due to COVID-19 and the challenges in the current system. It also provides details of lessons for other countries from India’s experience with MGNREGA.

The COVID-19 pandemic and the resulting lockdown in India had a dire effect on employment and income across the country. The Government of India attempted to mitigate the impact by announcing various relief measures under the Pradhan Mantri Garib Kalyan Yojana (PMGKY). Under PMGKY, the GoI worked to provide relief to a large number of unemployed persons, including migrant workers, who had returned to their villages. These relief measures were channeled through the government’s flagship cash-for-work program, Mahatama Gandhi National Rural Employment Act (MGNREGA). It increased the daily wage rate of workers from USD 2.44 (INR 182) to USD 2.70 (INR 202) and subsequently increased its budget allocation.

MSC (MicroSave Consulting) undertook a mixed-method study [2] the impact of COVID-19 on the income of low-income households and assessed the government’s COVID-19 relief package, Pradhan Mantri Garib Kalyan Yojana (PMGKY). The study covered the effect of the steps taken under MGNREGA. The first and second phases of the study were conducted respectively in May, 2020 during the three-month complete lockdown and in September, 2020, after the lockdown norms were eased. The study covered 1,165 MGNREGA beneficiaries in Round 1 and 1,186 beneficiaries in Round 2 across 18 states and union territories.

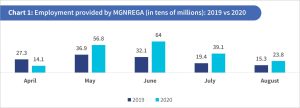

The government tried to absorb as many people under MGNREGA as possible. However, the significantly high demand for work made the task challenging. In just 50 days, between 1st April and 20th May, 2020, 3.5 million workers sought employment under the program. In comparison, in the year 2019-20, 1.5 million workers had applied for MGNREGA jobs. Addressing the higher demand, the government provided more work as illustrated in Chart 1, which compares the number of person-days[3] generated under MGNREGA in 2019 against those in 2020. Except in the month of April, 2020 when the lockdown restricted work, person-days generated in 2020 were much higher than in 2019. As per official data, only 15% of households enrolled under the program reported receiving work in round 1 of our study, which increased to 53% in round 2.

One of the biggest achievements of the scheme was that it provided work to women in rural areas. While the Indian government mandates a minimum of one-third participation by women in MGNREGA, 53% of the persons employed under MGNREGA were female in the fiscal year 2020-21.[4] Additionally, MGNREGA is implemented by local panchayats[5], which must have 50% women representatives. Reservation for women in the program and in its implementing body have led to a massive increase in participation by women.

The government also attempted to make timely payments to the workers. In May, 2020, 40% of respondents reported that they had not received their pending MGNREGA wages so far. In September, 2020, the government ensured that it cleared all dues as 83% respondents reported that they had received all payments pending for the work done in preceding months. According to official data, 87% of the total payments in 2020-21 have been paid.

The government attempted to absorb more people under MGNREGA. However, due to the excessive demand for jobs created by the pandemic, the program could not accommodate everyone. One respondent said, “If 20 people are required for a specific job, more than 200 are available to do the work.” As a result, 31% of respondents who were enrolled in MGNREGA did not receive work after applying.

As more labour was available during the lockdowns, project completion was much quicker under the program. This reduced the number of days required to complete a project—thus reducing the number of days a person was employed and earned wages. Only 7 million of the 75 million employed under MGNREGA received work for full 100 days in the year 2020-21.

What could have been better?

MGNREGA shouldered some of the adverse effects of the pandemic, providing much-needed employment and income to returning migrants and other vulnerable segments. Its efficacy as a tool to address future economic shocks are likely to improve if some of its design and implementation issues are solved.

- The scheme is unable to entirely absorb the high demand for jobs created during economic crises. As a result, job seekers do not receive the guaranteed 100 days of work. The government should cater to any surge in employment demand by creating new avenues of employment and expanding areas of permissible work. MGNREGA workers could be employed gainfully in short-staffed positions. For example, they could be instrumental in guarding national parks and forests.

- Although the GoI raised the daily MGNREGA rate, it should increase further to match the minimum wage rate in each state. The wages paid under the program continue to be lower than the minimum wage rate in 17 states in the country. To do this, the government should increase the budget allocation for the program. The country appears to be moving in the right direction as the allocation for this scheme increased in the 2021-22 Union Budget by 19% compared to the 2020-21 allocation.

- While irregularities and delays in MGNREGA payment have reduced, these issues can be minimized further through investments in human resources and technology and adoption of automated processes. The Mobile Monitoring System (MMS) should be used across all village councils to update the database on demand submission, work allocation, attendance, and measurement of work. Through these steps, the GoI can curb administrative delays at every stage to provide beneficiaries their dues on time.

- By design, MGNREGA is only made available to those living in rural areas, which leaves out vulnerable populations in cities. The pandemic dealt a devastating blow to the urban poor. Yet, they were unable to seek employment relief from the government.[6] The pandemic has categorically highlighted the need for an employment guarantee scheme for the urban poor. The government could employ, for instance, urban workers in municipalities to ensure cleanliness and sanitation, and in the process solve the dual problems of unemployment and poor sanitation.

- Relief provided through MGNREGA or direct income support provides some immediate assistance. Yet it often fails to sufficiently protect the vulnerable from the next shock. As India experiences a second wave of COVID-19 and experts predict a third wave, the government should be prepared with a plan that absorbs the unemployed population. It must also create policies and guidelines for industries to ensure the safety of its workers through the provision of shelter and food so that a huge segment of the population is not forced to return to their villages again.

Lessons for other countries from India’s experience with MGNREGA

Many countries and humanitarian organizations launched cash-for-work programs as a COVID-19 relief measure. India’s 16 years of experience with MGNREGA as an employment support program and now as a COVID-19 relief measure may help budding cash-for-work programs across the globe.

- Maximum coverage: Cash-for-work programs should ensure coverage of all vulnerable segments, especially during times of crises. The Indian government worked to cater to the rising unemployment and income loss in the country through MGNREGA. However, it could not provide relief to the urban poor as they are not covered under MGNREGA. Similarly in Kenya, the national cash-for-work program, Kazi Mtani continues to target rural youth exclusively. Due to suboptimal coverage, the urban poor are unable to access such relief measures.

- Gender-inclusive design Economic crises often have a disproportionate impact on women. In our study, households where the primary wage earner is female were reportedly less likely to get reemployed once lockdown restrictions were eased.[7] Governments must ensure that its programs can provide adequate work and income to women. The Indian government mandates a minimum one-third participation of women in MGNREGA. Countries should provide reservation to women in programs and implementing bodies of those programs. They should also ensure the nature of work provided is favorable for them.[8] The World Food Program ensures 60% of those assisted are women in its cash for work program in Tajikistan.

- Inclusive program design: India employs a localized system where unemployed persons can approach their panchayat to volunteer for MGNREGA work. This allows unrestricted access to every household. Contrastingly, the Pre-employment Card Program announced in Indonesia as a COVID-19 relief measure required individuals to register online. This feature faced criticism as people with low socioeconomic status and low educational levels are less likely to have internet access.[9] Informal workers tend to fall under these demographics, making them less likely to have access to the internet and thus, the program. While digitizing programs, governments should create offline measures too to ensure the most vulnerable are not left out.

- Transparent system with a strong GRM (Grievance Resolution Mechanism): Communication and lack of awareness remain real problems across the globe. Governments should ensure workers have full knowledge of the amount and timing of payment of wages. They should be able to ask for timely resolution in case of irregular, insufficient, or delayed payments. MGNREGA has an online GRM portal, a publicly available complaint register, and a portal to see the status of complaints. However, the awareness and use of such mechanisms is low among beneficiaries.

Developing nations can use these lessons to better serve their unemployed and low-skilled workers.

MGNREGA (Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Act) is GoI’s social security program that guarantees at least 100 days of employment to unemployed, low-skilled workers.

[1] MGNREGA (Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Act) is GoI’s social security program that guarantees at least 100 days of employment to unemployed, low-skilled workers.

[2] Detail methodology can be read here.

[3] Person-days is the number of people working per day times the number of days worked.

[4] The percentage of female participation has decreased slightly from 56% in 2016-17 to 53% in 2020-21.

[5] A Panchayat is a key village level government institution responsible for fulfilment of the community’s aspirations with respect to development of the village. It usually consists of five respected village elders.

[6] CMIE (Center for Monitoring Indian Economy) reported the unemployment rate in India in September, 2020 to be 5.88% in rural areas while 8.45% in urban areas.

[7] 17% of households with male primary wage earners reported an increase in income after the lockdown restrictions were eased while only 8% households with female primary wage earners reported the same. 10% households with male primary wage earners could get employed again while only 5% households with female primary wage earners could do the same.

[8] In rural areas, most women are unable to travel far from their houses so the work should be available within a 5km radius.

[9] Source: Survey by Indonesia Internet Service Provider Association 2017

by

by  May 28, 2021

May 28, 2021 7 min

7 min

Leave comments