SIBs can make development spending more effective

by Tomojit Basu

Oct 29, 2021

4 min

Impact bonds are a promising new tool that can help India’s central, state, and local governments take up innovative and scalable catalytic projects.

In late 2019, the IFC estimated an annual gap in Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) financing worth nearly USD 2.5 trillion in developing countries.[1] According to the OECD, the COVID-19 pandemic increased this shortfall by USD 1.7 trillion in 2020. This amount included a gap of USD 1 trillion in pandemic recovery measures by advanced economies. In June 2021, estimates indicated that India needed USD 2.64 trillion to meet the SDGs by 2030. While fiscal budgets will remain crucial to meet SDGs, the widening financing gaps highlight the case for private capital to support development outcomes.

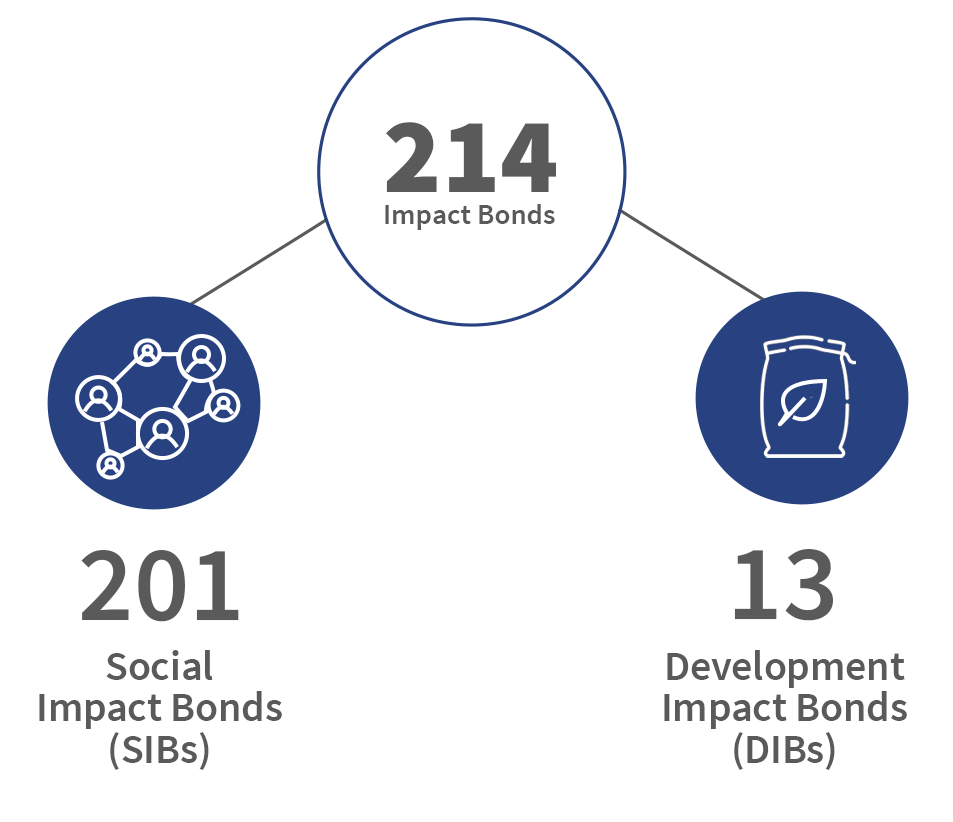

Results- or outcomes-based financing (RBF or OBF) are an essential mechanism that can help private actors contribute considerably to development goals. Impact bonds are a specific RBF approach that has gained traction over the past decade. They are outcomes-based contracts where private investors provide upfront capital for a development project or service. They are repaid with interest only if the project achieves pre-defined results, evaluated by a third-party assessor. Social impact bonds (SIBs) and development impact bonds (DIBs) shift the focus of development projects from activities and inputs to outcomes. They connect outcome payers,[2] service providers, and private investors to deliver measurable impact within specified timeframes. Impact bonds align risks and social returns and create incentives for all stakeholders, particularly investors, to ensure efficient project execution and rigorous monitoring and evaluation.

Impact bonds have been used across various thematic areas—healthcare, education, clean water and sanitation, climate change, and skilling and employment.

The potential role for SIBs in India and the developing world

Pandemic-induced public spending has increased fiscal deficits and constrained the short-term development budgets of several countries, such as India. National and sub-national governments can consider using SIBs to overcome this hurdle for specific interventions for which outcomes can be quantified. The arrangement facilitates financial risk-sharing and encourages fiscal prudence as payments are made if outcomes are delivered. Moreover, governments get the necessary lead-time before payouts, as contracts typically last over a reasonable timeframe, often between three to five years. Forecasts depict macroeconomic conditions to stabilizing and improving over that timeframe.

SIB projects differ from traditional government-led ones—they shift the focus of funding from inputs and activities to outcomes. Government-led projects often remain constrained by political prerogatives or rigid procurement and partner selection processes. They tend to be risk-averse at the cost of innovation, unlike SIBs. Hence, government projects generally deliver sub-optimal results in terms of service delivery, meeting budgeted costs and timeframes, and beneficiary targeting. They may fail to address critical needs, such as improving learning outcomes among primary school students or optimizing maternal nutrition. Project failure in such cases sets backs the development impact by years.

SIBs can enable innovation by investing in smaller-scale yet catalytic projects. They provide the initial risk capital to identify successful models that governments can later scale. The multi-stakeholder nature of the approach also facilitates accountability. The interplay between innovation and stakeholder cooperation can help develop new design and development models using a results-based framework. These models can lead to more effective outcomes while assuring double bottom returns for investors.

The Pimpri-Chinchwad Municipal Corporation (PCMC) in Maharashtra has taken the lead in SIBs. It signed an MoU with the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) in December, 2020 to co-create India’s first SIB to deliver quality, affordable, and accessible healthcare. PCMC will cover costs only if pre-defined targets are met, which limits the risk of inefficient and ineffective spending. Governments can also learn from other successful IB-backed programs, such as the Educate Girls Development Impact Bond in Rajasthan that delivered spectacular impact three years after implementation. The program helped students achieve 160% of final learning targets and surpassed the enrollment target at 116%.

Local and state governments need to identify similar projects to scale up that address fundamental development gaps. SIB-backed projects can create a virtuous cycle[4] of investment commitments. The investment will lead to successful outcomes, led by strong data-driven management and rigorous evaluations. The cycle will enhance the abilities of payers and service providers to attract capital. The approach would help public authorities optimize the use of resources and ensure timely delivery of services.

Aligning public-private effort

As of August 2021, developing countries had only 19 contracted impact bonds—12 DIBs and seven SIBs. The scope for growth in this market is considerable. India and many other developing nations already have relatively well-functioning approaches to public-private projects (PPPs) for significant infrastructure needs, such as the development of airports and roads. There are, however, few parallels in the realm of social infrastructures, such as co-developed healthcare facilities or educational institutions. Impact bonds, while not a panacea,[5] can help co-create scalable and catalytic PPPs to meet development aspirations.

Ultimately, the positive impact of utilizing innovative financing instruments like SIBs now could have long-term benefits. Governments must not allow constrained fiscal capacity to compromise welfare delivery. Prioritizing multi-stakeholder projects even if they are more localized can provide valuable lessons for development programming, funding, and implementation going forward.

[1] Doumbia D., Lauridsen M.L., p.2, Note 73, Fresh Ideas about Business in Emerging Markets, EM Compass (October 2019)

[2] SIBs and DIBs are distinguished by the outcome payer. Governments are outcome payers in SIBs while external donors, such as philanthropic organizations, government aid agencies, or multilateral institutions, are the outcome payers in a DIB.

[3] Gustafsson-Wright E. et al.; Social and development impact bonds by the numbers – July 2021 snapshot, Brookings Institution (July 15, 2021)

[4] Bohra L., Impact Bonds: An emerging market opportunity for innovative financing, ET Government (March 18, 2021)

[5] Nouwen C., Lee D. & Hornberger K., Five myths about impact bonds, India Development Review (May 5, 2020)

by

by  Oct 29, 2021

Oct 29, 2021 4 min

4 min

Leave comments