India’s enabling triangle for financial inclusion

by Graham Wright and Manoj Sharma

Sep 26, 2018

7 min

The blog discusses that successful efforts to foster financial inclusion involves three inter-related and mutually-reinforcing components.

In our earlier blogs, we expressed our concerns around the growth of the digital divide, as the focus for financial inclusion shifts to FinTech and superplatforms as “the definitive solutions”. While these solutions typically require smartphones, many of the poorer households in Asia and Africa simply do not have access to the devices. Neither do they have access to the bank accounts that are typically required to use the solutions effectively.

While there are potential solutions that could empower those without access to smartphones through the use of agents, it is also clear to us that successful efforts to foster financial inclusion involves three inter-related and mutually-reinforcing components. These are:

1. A national digital ID system, bank accounts, and, ideally, mobile phones for all

2. Bulk payments, which are typically government-to-people (G2P), to drive uptake and usage and thus foster trust in the digital ecosystem;

3. A seamless, interoperable payments system.

This is why everyone is so excited about the digital ecosystem currently under development in India. It combines these three elements. In this blog, we examine these in some detail:

1. A seamless, interoperable payments system

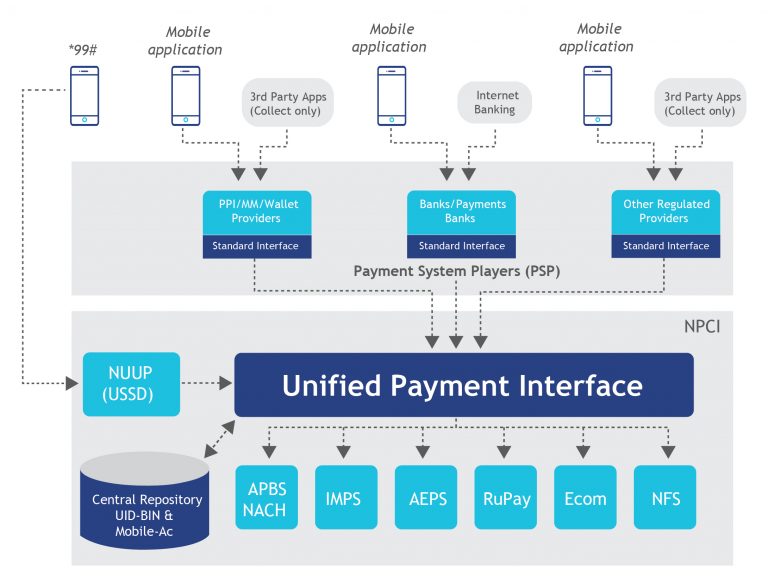

Unified Payments Interface (UPI): The UPI was developed by the National Payments Corporation of India (NPCI). The NPCI already operates the RuPay payments infrastructure as a lower cost rival to Visa and MasterCard to permit banks to interconnect and transfer funds. The NPCI was established by the RBI and Indian Banks’ Association (IBA) in April, 2009. It aims to consolidate and integrate India’s numerous payment systems and thus create national, standardised business processes for all retail payment systems.

The UPI provides a single, digital interface across all systems for smartphones (but not feature phones) linked to bank accounts. It provides users with the ability to make payments using 1-click 2-factor authentication, using just a personal smartphone without requiring any acquiring (swiping) devices or physical tokens. The diagram below illustrates this in detail.

To do this, the UPI allows a unique digital identifier for every bank account in the country, which can then be used to send money using India’s existing Immediate Payment Service (IMPS). The unique identifier is almost like an email address or an assigned name as well. It allows users to transfer money 24/7 and instantaneously to any other account in the country without requiring either a digital wallet, a credit card, or a debit card.

As a result, UPI users can make payments simply by exposing their unique identifier (the Virtual Payment Address (VPA) without sharing account details. The UPI also offers both individual users and business entities with the ability to send payment or “collect” requests to others with a “pay by” date. Users can also delay payment requests for later payment before the collection expiry date without having to block the money in their accounts. Users can, therefore, use their mobile phone to “pay” someone (push) as well as to “collect” from someone (pull). In the future, users will also be able to pre-authorise recurring payments, such as for school fees, subscriptions, and utility bills, with a one-time secure authentication and rule-based access.

UPI offers a fully interoperable system that incorporates all players in the payment ecosystem without silos and closed systems, allowing users to transact from and to any bank. In the long-term, it is likely to result in the phasing out of debit and credit cards and point-of-sale devices—except perhaps in places where many foreigners frequent. Similarly, mobile wallets are likely to face a challenge from the rollout of UPI.

With the arrival of UPI, the 14 million merchants in India will be able to accept digital payments with ease. It has the potential to make every merchant, or indeed each individual, a cash-in and cash-out agent and accelerate the rollout of a “cash-lite” India. And, of course, both Google Pay and WhatsApp payment system are riding on UPI.

BHIM Aadhaar Pay BHIM Aadhaar Pay was launched in early 2017 to make payment to merchants with biometrics instead of relying on other form factors like phone, cards, etc. The merchants can download the app and, using a certified biometric scanner, accept payment. To make a payment, a customer simply needs to enter their Aadhaar number in the merchant’s app and select the bank from which they wish to make the payment. The customer’s biometrics, which is typically the fingerprint, is then used as the password for the transaction.

2. A national ID system and bank accounts for all

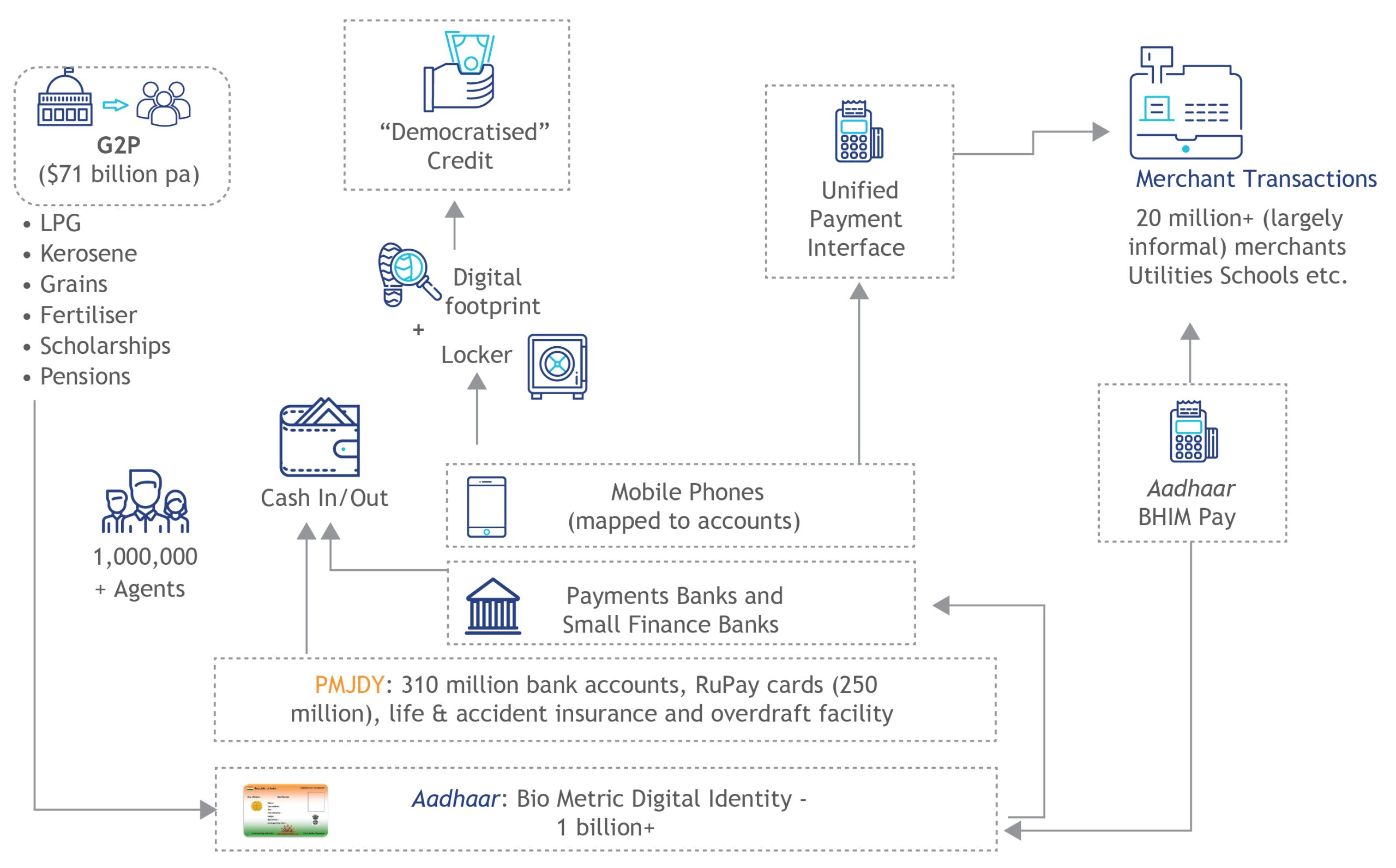

- The Aadhaar national biometric digital identity system. More than a billion Indians, well over 85% of the eligible population now have unique biometric digital identity cards. Their biometric data (fingerprints and iris scans) is held on a large database overseen by the Unique Identification Authority of India. Under the current regulations, this allows KYC/AML for basic account openingand for authenticating transactions. Aadhaar is the foundation for the India Stack (see below).

- The Pradhan Mantri Jan-Dhan Yojana (PMJDY): In 2015, the Government of India launched the PMJDY financial inclusion scheme to provide banking to all households without access to the formal financial system. PMJDY provides debit cards, insurance, pension facilities, and overdraft to beneficiaries. Within two years of the launch of the scheme, banks and their agentshad opened 310 million accounts. While MicroSaveestimates that around a third of these were opened by people who already had another bank account, the impact in terms of access to basic banking services was impressive. PMJDY-2.0 was launched in August 2018 with enhanced benefits including the doubling of the overdraft limit to INR10,000 (USD139) and INR200,000 (USD2,778) accident insurance cover for RuPay cardholders.

- Payments banks and small finance banks: While almost all PMJDY accounts were opened by public sector scheduled commercial banks, the Reserve Bank of India (RBI) created two new types of banking licenses based on the Mor Committee’s recommendations. Given the precarious state of India’s public sector banks, this looks like a prescient move. Payments Banks are permitted only to offer payments and limited savings servicesbut may not lend to their clients. These payments banks are expected to leverage digital technology to maximise their reach and minimise operational costs. In contrast, small finance banks were created to allow selected microfinance institutions to transform and begin to mobilise deposits from the low income, mass market.

- Mapping mobile phones to bank accounts and the India Stack: The next key part of the development of the ecosystem will be to map account holders’ mobile phones to their bank accounts. The mapping exercise will allow them to conduct transactions and begin to fill their “digital locker” with transaction data from their phones, as well as other Aadhaar enabled devices. This key data will complement other key records, such as education certificates and land titles, also stored in the locker – thus creating a “digital footprint” to inform financial service providers.

An ever-increasing proportion of India’s adult population now owns smartphones – a figure that is set to rise to 50% by 2020. Those with smartphones will, (subject to trust and connectivity issues) be able to use the UPI. The UPI will allow both push and pull transactions, using basic identifiers similar to email addresses or telephone numbers. Currently UPI is free, thus removing the need for merchant discount rates and other charges for making payments. This effectively enables merchants and individuals to use the UPI in the same way as they currently use as a point-of-sale device to effect transactions and receive payments.

All these paperless, presence-less, cashless transactions will create a digital footprint, stored in the user’s digital locker. The India Stack offers open application programming interfaces (APIs), which thus encourages the full force of local and international creativity to leverage the ecosystem and offer value to users in a variety of ways.

3. Bulk payments – typically government-to-people (G2P) payments – to drive uptake and usage and thus foster trust in the digital ecosystem

Government-to-people (G2P) Payments: The Government of India transfers around USD 71 billion to its citizens every year. These transfers comprise cash as benefits and pensions, as well as kind as grains, kerosene, and fertilisers, among others. This provides a tremendous opportunity to kick-start financial inclusion by using these transfers to seed digital money into bank accounts. Furthermore, the savings that arise from digitising these payments and linking them to biometric identity are breath-taking – and enough to pay for the cost of rolling out Aadhaar every 4-6 months. The estimates of what is quaintly referred to as “leakage” suggest that for many schemes, as much as 40% of the amount transferred does not reach the intended beneficiaries.

However, there are a surprising number of challenges to digitising G2P payments effectively. These range from the basic need to link bank accounts to Aadhaar numbers, to ensuring that there are adequate agents and retail outlets. The availability of adequate outlets would allow beneficiaries to cash-out and then buy grains and other items if their benefits are transferred directly in cash to their bank accounts.

These three ingredients come together in India’s remarkable digital ecosystem to create the basis for not just financial inclusion but to create digital footprints for the poor. This begins the journey to “democratised credit” – as the diagram below highlights.

Each of these three key ingredients plays a synergistic role:

- National ID, bank accounts, and mobile phones provide the foundational layers and channels for people to enter and participate in the digital financial ecosystem;

- Bulk payments (typically G2P transfers) push the digital value into these accounts and thus encourages their use and development of trust in digital money as opposed to paper money;

- Based on this, the seamless, interoperable payments system encourages further use of digital money, thus building the digital footprints that will allow people to participate fully in the financial system, and to derive real economic value from it.

- Each of the three is essential to achieving meaningful financial inclusion – as we have seen that simply opening bank accounts is not enough.

Written by

Graham Wright

Group Managing Director

by

by  Sep 26, 2018

Sep 26, 2018 7 min

7 min

Leave comments