Progress and Challenges with KYC and Digital ID

by David Cracknell and Venkat Attaluri

Sep 4, 2017

7 min

The blog highlights the progress and challenges with KYC and digital identification

Based on great inputs and discussions from Amrik Heyer, FSD Kenya, Stephen Mwaura, former Head of Payments, Central Bank of Kenya, Uma Shankar Paliwal, Former Executive Director, RBI, Dennis Njau, Head of Channels, Kenya Commercial Bank, Gang Chai, Payment Policy Manager, Central Bank of Nigeria, and Johnah Nzioki from Eclectics.

“Identification provides a foundation for other rights and gives a voice to the voiceless.” – Makhtar Diop, World Bank Vice President for Africa

At a recent workshop organised by The Helix Institute, leading DFS industry players, including providers, regulators, aggregators, and technology providers, came together to deliberate on innovative ways of addressing the key challenges that face agent networks. They split up into three groups to look at the key issues in the context of 1) policy and regulation, 2) strategy and market evolution, and 3) operations.

This blog post details observations from the policy and regulation group, as listed in the following section.

Digital Financial Services has Driven Financial Inclusion

Premised on digital and mobile solutions, Digital Financial Services (DFS) has transformed the landscape of the financial sector. It has brought about increased efficiency, convenience, and consumer options. DFS has increased access to financial services for a population that has hitherto been financially excluded. As per GSMA’s 2016 State of the Industry Report-Decade Edition, there are 500 million registered mobile money accounts globally, of which 118 million are active (on the basis of at least one transaction in 30 days). The number of active mobile money agents (on the same basis) stands at 2.3 million.

Large Numbers Still Lack KYC Compliant Identification

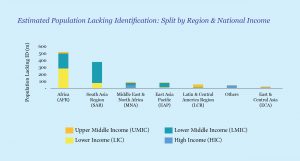

Historically, opening a bank account in many markets has proved to be a challenge due to Know Your Customer (KYC) guidelines, which require proof of identity and address. Unbanked groups often suffer disproportionately as a result of their inability to offer proof of identity. Such identification is generally based on birth certificates and passports, and proof of address based on utility bill payments. Over a billion (17.7 %) of the world’s population [1] remain unable to meet official KYC requirements. The World Bank ID4D 2017 Global data set shows the estimated population that lack identification, as seen in the adjoining graph.

People who fail to meet KYC requirements are excluded from accessing formal financial services, including savings accounts, loans, remittances, insurance, and pensions, among others. However, the problem goes deeper, and often such people are unable to digitally receive benefits from the government, including payments for social security, basic health care, and primary and secondary education. Lack of identification also prevents them from receiving international remittance through formal channels.

Lack of KYC Compliance Impedes Mobile Money and Agent Banking

Volume is the main factor that drives the business-case for institutions that offer digital financial services. This means that providers must increase their customer base and focus on onboarding large numbers of new customers – a process that becomes easier if simple and effective ways to satisfy KYC requirements are introduced.

KYC Acts as a Multipurpose Enabler

Conversely, the existence of KYC-compliant documentation that enables efficient onboarding of customers can have a number of enabling effects. These include a) facilitating mechanisms that may not require a branch, b) allowing harmonisation of government databases for Government-to-Person (G2P) payments, c) enabling transaction mechanisms that do not require signatures, and d) facilitating access to tailor-made financial services suited to a range of customer groups.

Identity Comes in Several Forms

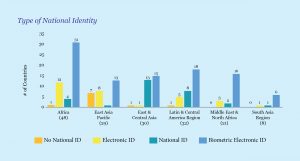

The World Bank ID4D 2016 data set (see adjoining graph) indicates the progress of national identity card systems of various countries and regions as per the World Bank Group’s Identification for Development initiative.

The KYC Journey Often Starts with Simplified KYC Requirements

In most markets, subscribing to mobile money is easier than opening a bank account. The required level of KYC varies between mobile money and bank accounts. Higher levels of KYC are usually required for opening bank accounts due to the higher transactional value and volumes, as well as nature of banking products. This is a key reason for the growth of mobile money when compared to agent banking in many markets.

Simplified KYC can Enable Limited Access for Large Populations

Countries without national identification have sometimes introduced simplified KYC guidelines to enhance financial inclusion. This includes restrictions on transaction values (deposits/withdrawals/transfers) to mitigate anti-money laundering (AML) risks. In such cases, if customers wish to upgrade from a simplified KYC account, they need to provide full KYC-compliant documentation to their financial institution.

Pradhan Mantri Jan-Dhan Yojana (PMJDY), India’s national mission for financial inclusion, ensures access to financial services through simplified KYC requirements. In almost three years, 290 million accounts have been opened under the scheme, with 60% of accounts in rural and semi-urban areas. These accounts hold USD 9.9 billion worth of savings, which translates to an average balance of USD 34.

The financial Sector may Create Financial Identity, but It Would Likely be Insufficient

Challenges in the rollout of national identification forced the Nigerian banking sector to provide all banked customers with a Bank Verification Number (BVN). Enrolment of BVN involves capturing a customer’s details, including fingerprint and facial image, after which a BVN is generated. The BVN is expected to minimise the incidence of fraud and money-laundering in the financial system and enhance financial inclusion. Prior to the introduction of national identity, Bank of Uganda mandated the Credit Reference Bureau (CRB) to create a financial identity card and to link to CRB. After signing up an initial 900,000 customers, 150,000 customers were being added annually. As it turned out, the financial identity card in Uganda was not sufficient, nor was it designed to drive financial inclusion [2].

Simplified KYC and/or Financial Sector Identification is Often a Stage in the Path to Full Financial Access

Equity Bank in Kenya has observed that customers conduct more than double the number of transactions at agents when compared to transactions at the bank branch and ATMs, while self-initiated transactions conducted on customers’ mobile devices amount to four times those made at agents.

Meeting KYC Requirements is a Particular Challenge for Refugee Populations

By the end of 2015, war, conflicts, and natural disasters had forcefully displaced an unprecedented 65 million [3] people around the world. Refugees and displaced populations face great challenges in obtaining formal identity and proof of residence, and often fail to meet KYC requirements. A few countries, including Egypt, Zambia, and Uganda, have allowed refugees to open mobile wallets using government attestation cards or through UN refugee registration cards issued by UNHCR. However, regulators report that providing identification to refugees needs careful application due to Anti Money Laundering and Combating the Financing of Terrorism regulations and acts.

Fragmentation of Records Pose Challenges to Digitising Identity

For many governments, the evolution from paper-based identity to digital identity proves challenging. It requires a huge capital investment to create a national database and to remove duplicate records from multiple existing databases so that there is a single identification number per individual.

Digital Identification can Facilitate Rapid On-boarding and Competition among Providers

Access to national identification databases varies from country to country. Yet, the drive for financial inclusion requires regulated financial institutions to be able to avail digital access for free or for a low fee. Government and private institutions in Kenya have been progressing with an Integrated Population Registration System (IPRS), a central database to verify the identity of a citizen and residents. Commercial banks, telecommunications companies, and other institutions are digitally linked to the National Population Register of the IPRS and have been using this information for efficient customer on-boarding.

Given that on-boarding customers is easier with digital identification, competition can be facilitated by removing barriers, not only to on-boarding but also to the movement of customers. For instance, in India, the IndiaStack API has been designed to use unique digital infrastructure that links a biometric identity (known as Aadhaar) combined with a digital locker that contains customer documents and certificates, to enable banks to provide competing loan offers to potential customers without submitting any physical documents.

Is there a Balance between Customer Protection/Privacy and Data Sharing of Digital Identification?

In the cases where governments have allowed public and private institutions to access the digital ID database, it is important to decide the extent of information that should be shared with various institutions. Such information ranges from complete details about the individual, including full KYC, to top-level verification that safeguards the privacy of citizens. For instance, in India, the government has not limited Aadhaar to being a means of identification to deliver government subsidies and services alone. Private agencies like financial institutions or telecom companies can use Aadhaar for the purpose of electronic KYC, which replaces the physical proof of identity/proof of address documents. Private players may also use Aadhaar to authenticate transactions based on biometrics. In other words, in the federated structure, the demographic data including biometrics reside with the government agency. Other agencies, including private ones, are allowed to fetch the required demographic data for KYC and biometric match-based confirmation to authenticate transactions on a real-time basis.

Conclusion

Digital identity and KYC, including tiered KYC, are vital components to on-board large numbers of unbanked and under-banked people to mobile money accounts and bank accounts in a rapid, cost-effective manner. With large populations possessing a digital account, and with digital identity being accessed by the government and financial and payment sectors, there is a distinct possibility that G2P payments, merchant payments, and technology-enabled financial services will show rapid evolution worldwide.

[1] The World Bank Group’s Identification for Development (ID4D) initiative

[2] Based on a presentation to the Alliance for Financial Inclusion

[3] UNHCR 2016

Written by

by

by  Sep 4, 2017

Sep 4, 2017 7 min

7 min

Leave comments