Keeping the channel happy for quick scale-up: A case from the Mumbai remittance market

by Ritesh Dhawan and Sakshi Chadha

Dec 1, 2014

5 min

In this blog, the authors share the results from a successful remittance market study conducted in Mumbai and conclude the sectoral implications of the current business model.

Remittances have emerged as the most common anchor product offered by alternate banking channels, (banking channels used by the unbanked such as money transfer agents), particularly in large Indian cities like Delhi and Mumbai. Huge unmet demand for sending money home efficiently and quickly, combined with a willingness to pay for the service, has made over the counter (OTC) remittances an attractive proposition for many digital financial service providers. Competition in this space has increased tremendously and every provider is keen to hold on to an increase, their share of the pie.

The delivery channel for remittance services comprises a range of stakeholders from the bank to the front-line agent and all the managers and facilitators in between. Such is the importance of the channel offering remittances that the provider chosen to make the remittance is often not decided by the customer, but rather by the front-line agent, who makes the decision based on the commission he/she will receive. Customers sending money using OTC are often oblivious of the provider used to send their money. Their primary concern is confirmation that money has reached the intended beneficiary.

Recently the OTC remittance business in Mumbai has caught the eye of First Rand Bank (FRB) a multinational bank, which has entered into this arena with an innovative and disruptive business model that focuses on keeping the channel happy. The business model, which is still in its nascent phase, has been (according to transaction agents and distributors) efficient enough to wrest nearly 20% of the business from well-established Business Correspondent Network Managers (BCNMs) within six months of the bank entering the OTC market.

Practices adopted by the new entrant (what we observed)

· Competitive channel compensation: One of the reasons for M-PESA’s remarkable take-off in Kenya was the generous commissions Safaricom paid to their channel in the start-up years in order to gain traction. For example, in 2010 the average agent received $420 commission per month. Since M-PESA has become so well entrenched, and with the growth of the agent network, this had fallen to $129 by 2013. In Mumbai FRB gained much-needed traction and, in turn, made in-roads into the well-established remittance market by offering better compensation to channel partners. Master agents or “distributors” and front-line agents were offered lucrative commissions to attract the early adopters among them. Below is a brief comparison based on the feedback we received from the field.

Direct involvement of the bank in channel recruitment: In this model, the bank has done away with BCNMs and is directly recruiting distributors and agents in the field. The bank carries out extensive due diligence prior to finalizing the distributors. They target distributors who have worked with other providers since they already have an agent network working for them. This experience of distributors is then leveraged for agent selection. A team from the bank is deployed on the field to monitor the agent selection process, conduct background checks, and assist the distributor in finalizing agent recruitment.

Advance credit limit to agents: Shortage of e-float at agent counters is a perennial issue that every provider grapples with – this has been repeatedly highlighted in The Helix’s agent network assessments (ANA) surveys across the globe. This problem becomes even more acute when the agent is unwilling to increase his/her liquidity with increasing business volumes. To ensure that a shortage of liquidity is no more a roadblock to scale-up operations, the bank has given a credit limit of Rs.5,000,000 (US$8,333) to its agents. This is given to the agents without any physical collateral or security deposit. And as the conservative eyebrows rise, it is worth mentioning here that there are a few (but only a few!!) mechanisms to prevent fraud.

Hourly reports: Distributors and the agents get hourly reports of all transactions. These reports keep the distributor informed of the cash position of the agent. The distributor’s field staff collects any excess cash from the agent. Instead of the traditional method of liquidity rebalancing, where the field staff member visits the agent counter only once a day, the frequency of visits to agent counter is not fixed and varies depending on the volume of business. This helps the distributor to collect cash and not leave the agent overloaded with cash. While in principle this collection exercise should be religiously followed on an hourly basis, non-adherence to this leaves the bank exposed to the risk of flight by the agent with large amounts of cash exchanged for e-float that has been taken on credit.

Distributor’s personal guarantee: Since this model is inherently exposed to cash risk, the bank has adopted some control measures. The bank has communicated that any fraud committed by the agents will be the distributor’s responsibility and reinforces this through constant in-the-field monitoring. This ensures that distributors are cautious during agent recruitment and also in cash management. Thus they recruit only those agents with whom they have an existing business relationship and can trust. The bank, through these measures, leverages the existing relations of the distributor and the agents to its benefit.

The bank, through its real-time monitoring framework, keeps a bird’s eye view on the entire business landscape. Whenever the cash balance increases beyond an acceptable level with any distributor, the bank intervenes to ensure that the cash is deposited in a timely manner.

MicroSave’s presentation to RBI in January 2014 highlighted that agent commissions and liquidity management are among the most important aspects that contribute to a sustainable agent network. With minor tweaks in the business model, FRB has made major in-roads into the well-established remittance market of Mumbai. This was made possible also because a portion of the channel commission is sourced through higher customer charges. MicroSave’s prior research suggests that customers are willing to pay for the service this sector offers.

Potential implications

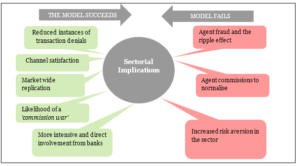

The market share that the bank was able to capture in such a short span of time guarantees that the tactics adopted has been observed by the competition. We are yet to see how the competition will react to the erosion of their market share. In the meanwhile, what we can assess are the potential implications for the sector. The figure below examines these in two eventualities – 1. Where the model succeeds and 2. Where it fails.

Written by

Ritesh Dhawan

Digital Finance Expert

by

by  Dec 1, 2014

Dec 1, 2014 5 min

5 min

Leave comments